2008 Annual Report

Congressional-Executive Commission on China2008 ANNUAL REPORT

Table of Contents

I. Executive Summary and Recommendations

Findings and Recommendations by Substantive Area

Rights of Criminal Suspects and Defendants

North Korean Refugees in China

2008 Beijing Summer Olympic Games

III. Development of the Rule of Law

Institutions of Democratic Governance

VII. Endnotes (incorporated into each section above)

Preface

The findings of the Commission’s 2008 Annual Report prompt us to consider not simply what the Chinese government and Communist Party may do in the months and years ahead, but what we must do differently in view of developments in China over the last year. We understand that China today is significantly changed from the China of several decades ago, and that the challenges facing its people and leaders are complex. As the United States engages China, it is also vital that our nation pursue the issues that are the charge of this Commission: individual human rights, including worker rights, and the safeguards of the rule of law. As China plays an increasingly significant role in the international community, this report describes how China repeatedly has failed to abide by its commitments to internationally recognized standards. Therefore it is vital that there be continuing assessment of China’s commitments. This is not a matter of one country meddling in the affairs of another. Other nations, including ours, have both the responsibility and a legitimate interest in ensuring compliance with international commitments. It is in this context, as Chairman and Co-Chairman of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China, that we submit the Commission’s 2008 Annual Report.

This year the international community watched with dismay as Chinese authorities responded with overwhelming force to a wave of public protests that spread across Tibetan areas of China. Amidst the astonishment with which people around the world more recently witnessed the spectacular opening ceremonies of the 2008 Beijing Summer Olympic Games and China’s effective management of the Games, Chinese authorities failed to fulfill several Olympics-related commitments—including commitments to press freedom, media access, the free flow of information, and freedom of assembly. The Chinese government’s and Communist Party’s continuing crackdown on China’s ethnic minority citizens, ongoing manipulation of the media, and heightened repression of rights defenders reveal a level of state control over society that is incompatible with the development of the rule of law. The cases of well over a thousand of the political and religious prisoners languishing in jails and prisons in China today are documented by the Commission’s publicly accessible Political Prisoner Database.

During the past 12 months, the Chinese government and Communist Party have outlined legislative and regulatory developments in areas such as anti-monopoly, open government information, collective contracting, employment promotion, regulation of the legal profession, and intellectual property, among others. Based on China’s record of past enforcement, these new measures will require consistent and transparent implementation if they are to fulfill the government’s stated objectives. China’s record on human rights and the development of the rule of law over the last year continued to reflect the following troubling trends: (1) heightened intolerance of citizen activism and suppression of information on matters of public concern; (2) ongoing instrumental use of law for political purposes; (3) stepped up efforts to insulate the central leadership from the backlash of national policy failures; and (4) heightened reliance on emergency measures as instruments of social control. The Chinese government and Communist Party continue to equate citizen activism and public protest with "social instability" and "social unrest." China’s increasingly active and engaged citizenry is one of China’s most important resources for ad-dressing the myriad public policy problems the Chinese people face, including food safety, forced labor, environmental degradation, and corruption. Citizen engagement, not repression, is the path to the effective implementation of basic human rights, and to the ability of all people in China to live under the rule of law.

Sander M. Levin, Chairman Byron L. Dorgan, Co-Chairman

General Overview

Over the last year, the following general trends with regard to human rights and the development of the rule of law have been evident in China:

- The Chinese government’s and Communist Party’s intolerance of citizen activism increased, as did the suppression by authorities of information on matters of public concern.

- The instrumental use of law for political purposes continued, and intensified in some areas, notwithstanding developments in areas such as death penalty reform, anti-monopoly, open government information, employment promotion, and collective labor contracting.

- Official efforts to insulate the central leadership from the backlash of national policy failures continued, as efforts to prevent "sensitive" disputes from entering legal channels that lead to Beijing intensified.

- In the wake of Tibetan protests, the Sichuan earthquake, the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games, and, most recently, a food safety crisis involving tainted milk products, the stake that Chinese citizens and citizens of other countries have in improved governance in China continued to rise. The Chinese government’s and Communist Party’s increasing reliance on emergency measures as instruments of social control over the last year underscored the downside risk of insufficient or ineffective rule of law reforms.

INTOLERANCE OF CITIZEN ACTIVISM

The clearest manifestations of Chinese government and Communist Party intolerance of citizen activism during the past year were the detention, "patriotic education," isolation, and deaths of Tibetans following protests in Tibetan areas of China. Authorities failed to distinguish between peaceful protesters and rioters as required under both Chinese law and international human rights norms. Heightened intolerance of peaceful protest also was evident in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR) in the aftermath of demonstrations in Hoten and amid security preparations for the 2008 Olympic Games. Participants in the Hoten demonstrations protested government policies against a backdrop of rising controls and repressive measures in the XUAR, including wide-scale detentions, restrictions on Uyghurs’ freedom to travel, and heightened surveillance over religious activities and religious practitioners.

Illegal detentions and harassment of dissidents and petitioners followed the Chinese government and Communist Party’s instructions to officials to ensure a "harmonious" and dissent-free Olympics. Individuals detained for circulating a "We Want Human Rights, Not Olympics" petition are now serving sentences in prison and "reeducation through labor" (RTL) centers. The government designated special locations or "zones" for public protest during the 2008 Olympic Games, but no protests received approval, and the harassment of applicants for protest permits has been reported. Authorities also harassed legal advocates connected to religion-related cases and active in defending religious groups. Such harassment intensified in the run-up to and during the 2008 Olympic Games. Advocates and rights defenders were placed under 24-hour police surveillance during the resumption of the U.S.-China Human Rights Dialogue held in Beijing, and also during a visit to Beijing by Members of the U.S. Congress. Central and local officials also tightened controls over political organizations and political party figures affiliated with parties other than the ruling Chinese Communist Party. Central authorities took steps to quell burgeoning public discussion of the merits of eliminating or phasing out the one-child population planning policy. Authorities targeted a number of HIV/AIDS and other health advocacy organizations, and shut down or removed content from their Web sites.

INSTRUMENTAL USE OF LAW FOR POLITICAL PURPOSES

Chinese authorities’ use of law as an instrument of politics continued unabated, and intensified in some areas. Provisions in Internet regulations that prohibit content deemed "harmful to the honor or interests of the nation" and "disrupting the solidarity of peoples," supplied "legal" justification for the censorship of Internet content deemed politically sensitive. The crime of "inciting subversion of state power" under Article 105, Paragraph 2, of the Criminal Law continued to be a principal tool for punishing those who peacefully criticized the Chinese government or who advocated for human rights on the Internet. Chinese government authorities particularly targeted persons who openly tied their criticism to China’s hosting of the 2008 Olympic Games or handling of the Sichuan earthquake. Legal provisions that prohibit the incitement of others "to split the state or undermine unity of the country" (Criminal Law, Article 103) have been invoked to punish Tibetans for peaceful expressions of support for the Dalai Lama or for their wish for Tibetan independence. Possession of a photograph of the Dalai Lama or a copy of one of his speeches continued to serve as evidence of "splittism." National and local measures regulating Tibetan Buddhism, and the Regional Ethnic Autonomy Law, prioritize fulfillment of government and Party political objectives and fail to protect Tibetan culture, language, or religion. Pursuant to a 1999 Decision of the National People’s Congress Standing Committee that established a ban on "cult organizations," the Chinese government continued to detain and punish Falun Gong practitioners and members of other spiritual and religious groups.

Legal provisions concerning national unity, internal security, social order, and the promotion of a "harmonious society" that were included in new legislation and regulations in 2006 and 2007 were invoked in cases of detention and imprisonment in the last year. China’s legal and judicial authorities continued to deny fundamental procedural protections (such as access to a lawyer or a public trial) to those accused of state security crimes. The number of cases in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of state security crimes, including cases involving peaceful expression or religious practice, remains high. Officials continued to use the charge of "illegal operation of a business" as a pretext to detain or convict individuals who publish religious materials or other materials deemed "sensitive."

The Chinese government requires Home Return Permits (HRP) for Hong Kong and Macau residents who are Chinese citizens to visit the mainland. The Chinese government confiscated the HRPs of citizens deemed prone to overstep the limits of "normal" or "approved" activities, and continued to deny the issuance of HRPs to 12 pro-democracy members of Hong Kong’s Legislative Council allegedly for their support of Tiananmen Square protesters in 1989 and their criticism of the Chinese government. In the past year, authorities confiscated, revoked, denied entry, or refused to renew or accept the passport applications of several known dissidents, and denied entry to a Hong Kong reporter covering the 2008 Olympic Games for a pro-democracy Chinese-language newspaper.

INSULATION OF THE CENTRAL LEADERSHIP FROM THE BACKLASH OF POLICY FAILURE

One objective of China’s new Law on Emergency Response, which took effect on November 1, 2007, is to "prevent minor mishaps from turning into major public crises" according to legislators cited in official reports. Shortly after the Sichuan earthquake in May, the Supreme People’s Court issued a Circular titled, "Completing Trial Work During the Earthquake Disaster Relief Period to Earnestly Safeguard Social Stability" instructing courts to "exercise caution in examining and docketing" cases that are "socially sensitive" or "collective" (e.g., multiple plaintiffs litigating collectively), and "to use mediation to achieve reconciliation through the withdrawal of charges to resolve disputes." In the wake of the earthquake, Party officials directed Chinese media and news editors to focus on "positive" stories that projected national unity and stability, and in the run-up to the 2008 Olympic Games ordered the media to avoid "negative stories" such as those relating to air quality and food safety problems.

Following Tibetan protests this spring, which involved thousands of protesters, Chinese authorities repeatedly placed blame on the actions of "a small handful" of "rioters" and "unlawful elements." The emphasis on "a small handful," combined with propaganda that holds the Dalai Lama personally accountable for events and developments, appears to be a strategy aimed at prompting Chinese citizens to rally around the government, and to pre-empt their pressing the government to explain the frustration and anger of the large number of Tibetan protesters. Authorities have revealed little information about the names of Tibetans detained, the charges (if any) against them, the locations of courts handling the cases, or the location of facilities where protesters have been or remain detained or imprisoned. As a result, China’s non-Tibetan citizens are even less likely than before to raise questions or complaints about China’s Tibet policy.

RISING STAKES OF LEGAL REFORM IN CHINA

In part due to China’s increasing engagement with the world economy, events within China have had an increasing influence on its neighbors and trading partners. Unsafe Chinese exports continue to demonstrate the rising stakes of China’s relative lack of government transparency, its weak legal institutions, and the Chinese government’s failure to enforce its own product safety laws. China’s global reach also affords the government an array of levers through which to reward overseas entities who support or remain silent on domestic Chinese human rights abuses, while penalizing those who criticize the Chinese government’s practices. China’s actions related to Darfur, Sudan, may be understood, at least in part, in this context.

Government and Party rhetoric warning against foreign influence became more strident in the last year. The Commission also observed detentions of ethnic minority citizens active in international arenas or perceived to have ties with overseas groups. In the past year, authorities targeted some Chinese religious adherents with ties to foreign co-religionists for harassment, detention, and other abuses. In the region along China’s border with North Korea, authorities reportedly shut down churches found to have ties with South Koreans or other foreign nationals.

The rising stakes of legal reform also became increasingly evident in the non-governmental organization (NGO) sector over the last year. China’s new Corporate Income Tax Law, which took effect on January 1, 2008, encourages public and corporate charitable donations through the provision of tax benefits. Increases in corporate donations and support for NGO activities in the wake of this year’s earthquake in Sichuan may have been attributable in part to these provisions. The majority of NGOs in China, however, regardless of their registration status, cannot engage in fundraising activities because charity-related laws only allow a small number of government-approved foundations to collect and distribute donations. This restriction posed significant challenges for the provision of victims’ support services in the aftermath of the May Sichuan earthquake, when unprecedented donations overwhelmed the government. China also is an origin, transit, and destination country for human trafficking. Chinese trafficking victims can be found in Europe, Africa, Latin America, Northeast Asia, and North America. Trafficking victims from Southeast Asia, the Russian Far East, Mongolia, and North Korea are trafficked to China, where victims are much in need of support services. The small number of government-approved foundations and the limited capacity to manage funds continued to impact the availability of victims’ support and social services.

Even as the Commission highlights these areas of concern, China over the past year has outlined a number of laws and regulations that have the potential to produce positive results if central and local government departments and Party officials prove their ability and willingness to implement them faithfully. Developments in areas such as anti-monopoly, open government information, collective contracting, employment promotion, regulation of the legal profession, and intellectual property, among others, are reported in detail in the pages that follow. The past year also marked the first time that Chinese courts mandated criminal punishment in a sexual harassment case, and issued a civil protection order in a divorce case involving domestic violence. And, as the Commission reported last year, the resumption of the Supreme People’s Court’s review of death penalty sentences was a significant development for China’s criminal justice system. Since January 1, 2007, when the death penalty reform took effect, the Chinese government has reported a 30-percent decrease in the number of death sentences. The Commission will continue to monitor the effectiveness of China’s implementation of the rule of law and human rights in the year ahead.

The Commission’s Executive Branch members have participated in and supported the work of the Commission. The content of this Annual Report, including its findings, views, and recommendations, does not necessarily reflect the views of individual Executive Branch members or the policies of the Administration.

I. Executive Summary and Recommendations

Rights of Criminal Suspects and Defendants | Worker Rights | Freedom of Expression | Freedom of Religion | Ethnic Minority Rights | Population Planning | Freedom of Residence | Liberty of Movement | Status of Women | Human Trafficking | North Korean Refugees in China | Public Health | Environment | Civil Society | Institutions of Democratic Governance | Commercial Rule of Law | Access to Justice | Xinjiang | Tibet

FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS BY SUBSTANTIVE AREA

A summary of findings for the last year follows below for each area that the Commission monitors. In each area, the Commission has identified a set of specific findings that merit attention over the next year, and, in accordance with the Commission’s mandate, a set of recommendations to the President and the Congress for legislative or executive action.

RIGHTS OF CRIMINAL SUSPECTS AND DEFENDANTS

Findings

- The rights of criminal suspects and defendants continued to fall far short of the rights guaranteed in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, as well as rights provided for under China’s Criminal Procedure Law (CPL) and Constitution.

- The Lawyers’ Law was revised to enhance the rights of criminal defense lawyers, but some provisions in the revised law conflict with the Criminal Procedure Law.

- Since the Supreme People’s Court (SPC) reclaimed its authority to review death penalty sentences as of January 1, 2007, the SPC has overturned 15 percent of all death sentences handed down by lower courts (through the first half of 2008). During 2007, 30 percent fewer death sentences were reportedly meted out, compared with the number of death sentences in 2006. The number of executions carried out annually remains a state secret, however.

- Chinese authorities continued to imprison individuals who were sentenced for political crimes, including "counter-revolutionary" crimes that no longer exist under the current Criminal Law. Individuals involved in the 1989 democracy protests are still being held in prisons in China.

- Misuse of police power and arbitrary detention remain serious problems. Police officers illegally monitored and subjected to arbitrary "house arrest" human rights lawyers and other ad-vocates in Beijing and elsewhere in connection with the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games.

- Local officials continued to abuse police power to suppress public protests. Following numerous clashes between police and civilians, the central government promulgated new rules that hold local officials responsible for misusing police power in "mass incidents" and for mishandling grievances.

Recommendations

- Sponsor technical assistance programs to support judicial reform and revisions to the Criminal Procedure Law and to ensure their effective implementation, with the aim of bringing China’s criminal justice system into conformance with the standards set forth in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

- Press the Chinese government to amend state secrets laws and related regulations that prohibit making public the number of executions carried out in China, and to implement such provisions effectively.

- Continue to call on the Chinese government to release those prisoners still in prison for counterrevolutionary and other political crimes, including those imprisoned for their involvement in the 1989 democracy protests, as well as other prisoners included in this report and in the Commission’s Political Prisoner Database.

WORKER RIGHTS

Findings

- Workers in China still are not guaranteed either in law or in practice full worker rights in accordance with international standards. China’s laws, regulations, and governing practices continue to deny workers fundamental rights, including, but not limited to, the right to organize into independent unions. Workers who tried to establish independent associations or organize demonstrations continue to risk harassment, detention, and other abuses. Residency restrictions continue to present hardships for workers who migrate for jobs to urban areas. Tight controls over civil society organizations hinder the ability of citizen groups to champion worker rights.

- Labor disputes and protests intensified during 2008. Management’s failure to pay wage arrears, overtime, severance pay, or social security contributions, were the most common causes. Social and economic changes, weak legislative frameworks, and ineffective or selective enforcement continue to engender abuses ranging from forced labor and child labor, to violations of health and safety standards, wage arrearages, and loss of job benefits.

- The discovery of an extensive forced labor network in Guangdong province this year revealed authorities’ inability to enforce basic protections for workers against China’s powerfully embedded labor trafficking networks.

- Three major national labor-related laws took effect this year: Labor Contract Law and new Employment Promotion Law took effect on January 1, 2008, and China’s new Labor Dispute Mediation and Arbitration Law took effect on May 1, 2008.

Recommendations

- Fund multi-year pilot projects that showcase the experience of collective bargaining in action for both Chinese workers and All China Federation of Trade Union (ACFTU) officials. Where possible, prioritize programs that demonstrate the ability to conduct collective bargaining pilot projects even in factories that do not have an official union presence.

- Expand multi-year funding for conferences in China on collective bargaining that bring together worker representatives, labor rights NGO representatives, labor lawyers, academics, ACFTU officials, and government officials.

- Support the production and distribution in various formats (print, online, video, etc.) of bilingual English-Chinese "how-to" materials on conducting elections of worker representatives, and on conducting collective bargaining.

- Fund projects that prioritize the large-scale compilation and analysis of Chinese labor dispute litigation and arbitration cases, leading ultimately to the publication and dissemination of bilingual English-Chinese casebooks that may be used as a common reference resource by workers, arbitrators, judges, lawyers, employers, unions, and law schools in China.

- Support capacity building programs to strengthen Chinese labor and legal aid organizations involved in defending the rights of workers.

FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION

Findings

- The Chinese government and Communist Party continued to deny Chinese citizens the ability to fully exercise their rights to free expression.

- The government and Party’s efforts to project a "positive" image before and during the 2008 Beijing Summer Olympic Games were accompanied by increases in the frequency and ex-tent of official violations of the right to free expression.

- Official censorship and manipulation of the press and Internet for political purposes intensified in connection with both Tibetan protests that began in March 2008 and the Olympics.

- Chinese officials failed to fully implement legal provisions granting press freedom to foreign reporters in accordance with agreements made as a condition of hosting the Olympics, and which the International Olympic Committee requires of all Olympic host cities.

- • The government and Party continued to deny Chinese citizens the ability to speak to journalists without fear of intimidation or reprisal.

- • Officials continued to use vague laws to punish journalists, writers, rights advocates, publishers, and others for peacefully exercising their right to free expression. Those who criticized China in the context of the Olympics were targeted more intensely. Restraints on publishing remained in place.

- • Authorities responsible for implementing a new national regulation on open government information retained broad discretion on the release of government information. Open govern-ment information measures enabled officials to promote images of openness, and quickly to provide official versions of events, while officials maintained the ability at the same time to cen-sor unauthorized accounts.

Recommendations

- Support Federal funding for the study of press and Internet censorship methods, practices, and capacities in China. Promote programs that offer Chinese citizens access to human rights-related and other information currently unavailable to them. Sponsor programs that disseminate through radio, television, or the Internet Chinese-language "how-to" information and programming on the use by citizens of open government information provisions on the books.

- Support the development of "how-to" materials for U.S. citizens, companies, and organizations in China on the use of the Regulations on Open Government Information and other records-access provisions in Chinese central and local-level laws and regulations. Support development of materials that provide guidance to U.S. companies in China on how the Chinese government may require them to support restrictions on freedom of expression and best practices to minimize or avoid such risks.

- In official correspondence with Chinese counterparts, include statements calling for the release of political prisoners named in this report who have been punished for peaceful expression, including: Yang Chunlin (land rights activist sentenced to five years’ imprisonment in March 2008 after organizing a "We Want Human Rights, Not Olympics" petition); Yang Maodong (legal activist and writer whose pen name is Guo Feixiong, sentenced to five years’ imprisonment in November 2007 for unauthorized publishing); Lu Gengsong (writer sentenced to four years’ imprisonment in February 2008 for his online criticism of the Chinese government); and other prisoners included in this report and in the Commission’s Political Prisoner Database.

FREEDOM OF RELIGION

Findings

- The Chinese government and Communist Party continued to deny Chinese citizens the ability to fully exercise their right to freedom of religion. The Chinese government continued in the past year to subject religion to a strict regulatory framework that represses many forms of religious and spiritual activities protected under international human rights law, including in treaties China has signed or ratified. The Chinese government continued its policy of recognizing only select religious communities for limited state protections, and of not protecting the religious and spiritual activities of all individuals and communities within China as required under China’s international legal obligations.

- Religious adherents remained subject to tight controls over their religious activities, and some citizens met with harassment, detention, imprisonment, and other abuses because of their religious or spiritual practices.

- The Chinese government and Communist Party sounded alarms against foreign "infiltration" in the name of religion, and took measures to hinder citizens’ freedom to engage with foreign co-religionists.

- President and Party General Secretary Hu Jintao called for recognizing a "positive role" for religious communities within Chinese society, but officials also continued to affirm the gov-ernment and Party’s policy of control over religion.

- • The central government’s "6–10 Office" (established in 1999 to implement the policy that outlaws Falun Gong) issued an internal directive to local governments nationwide mandating propaganda activities to prevent Falun Gong from "interfering with or harming" the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games. Beijing and Shanghai Public Security Bureaus also issued local directives providing rewards for informants who report Falun Gong activities to the police. Stories published in the state-controlled media, as well as statements made by Chinese officials, sought to link Falun Gong with terrorist threats in the lead-up to the Olympics.

Recommendations

- Include in China-related legislation and statements, calls for the Chinese government to guarantee freedom of religion to all Chinese citizens in accordance with Article 18 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

- Call for the release of Chinese citizens confined, detained, or imprisoned in retaliation for pursuing their right to freedom of religion (including the right to hold and exercise spiritual beliefs). Such prisoners include Adil Qarim (imam in Xinjiang detained during a security roundup in August); Alimjan Himit (house church leader in detention on charges of subverting state power and endangering national security); Gong Shengliang (founder of unregistered church who continues to serve a life sentence); Jia Zhiguo (unregistered bishop repeatedly detained by Chinese authorities and confined to his home since his most recent release from detention on September 18, 2008); Phurbu Tsering (Tibetan Buddhist teacher and head of a Tibetan Buddhist nunnery whom authorities detained in May 2008); Wang Zhiwen (Falun Gong practitioner who continues to serve a 16-year sentence for alleged crimes related to cults and acquiring state secrets); and other prisoners included in this report and in the Commission’s Political Prisoner Database.

- Support continued funding for non-governmental organizations that collect information on conditions for religious freedom in China and that inform Chinese citizens of how to defend their right to freedom of religion against Chinese government abuses. Encourage U.S. government-funded programs to orient priorities toward expanded coverage of different religious and spiritual communities within China.

ETHNIC MINORITY RIGHTS

Findings

- Authorities continued to repress citizen activism by ethnic minorities in China, especially within Tibetan areas of China, the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, and the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region (IMAR). [See findings for Xinjiang and Tibet for additional information.] In the past year, authorities in the IMAR punished ethnic minority rights advocates as well as citizens perceived to have links with ethnic rights organizations, intensifying a trend noted by the Commission in 2007.

- The government reported taking steps in the past year to improve economic and social conditions for ethnic minorities. It remains unclear whether such measures have been effectively implemented and include safeguards to protect ethnic minority rights and to solicit input from local communities. Ongoing development efforts in ethnic minority areas have brought mixed results for ethnic minority communities.

- The Chinese government continued in the past year to protect some aspects of ethnic minority rights. However, shortcomings in both the substance and the implementation of Chinese ethnic minority policies prevented ethnic minority citizens from enjoying their rights in line with domestic Chinese law and international legal standards. Ethnic minority citizens of China do not enjoy the "right to administer their internal affairs" as guaranteed to them in Chinese law.

Recommendations

- China-related legislation should include language that calls on Chinese authorities to formulate and implement China’s ethnic minority autonomy system in a manner that respects ethnic minorities’ "right to administer their internal affairs" as guaranteed to them in Chinese law.

- Call for the release of citizens imprisoned for advocating ethnic minority rights, including Mongol activist Hada (serving a 15-year sentence after pursuing activities to promote ethnic minority rights and democracy), as well as other prisoners mentioned in this report and in the Commission’s Political Prisoner Database.

- Fund rule of law programs and exchanges that raise awareness among Chinese leaders of different models for governance that protect ethnic minorities’ rights and allow them to exercise meaningful autonomy over their affairs. Support funding for non-governmental organizations to continue or develop programs that address ethnic minority issues within China, including task-oriented training programs that build capacity for sustainable development among ethnic minorities and programs that research rights abuses in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, as well as in other regions. (Also see recommendations for Tibet and Xinjiang.)

- Support funding for programs at U.S. universities to teach ethnic minority languages used in China, to better preserve these languages as the Chinese government implements programs to strengthen the use of Mandarin within China and to better prepare the international community to study and understand conditions for ethnic minorities in China.

POPULATION PLANNING

Findings

- The Chinese government announced that parents who lost an only child in the May 2008 Sichuan earthquake would be permitted to have another child if they applied for a govern-ment-issued certificate.

- The National Population and Family Planning Commission (NPFPC) issued a directive imposing higher "social compensation fees" levied according to income on couples who violate the one-child rule. Under the directive, urban families who violate the one-child rule risk having officials apply negative marks on financial credit records.

- Reports of forced abortions, forced sterilizations, and police beatings related to population planning policies continued. In some areas, government campaigns to forcibly sterilize women who have more than one female child included government payments to informants.

- A brief public discussion about the continued necessity of the one-child policy reportedly prompted the NPFPC Minister to issue a statement that China would "by no means waver" in its population planning policies for "at least the next decade."

Recommendations

- Urge Chinese officials to cease all coercive measures, including forced abortion and sterilization, to enforce birth control quotas. Urge the Chinese government to dismantle its system of coercive population controls, while funding programs that inform Chinese officials of the importance of respecting citizens’ diverse beliefs.

- Urge Chinese officials to release promptly Chen Guangcheng, imprisoned in Linyi city, Shandong province, after exposing forced sterilizations, forced abortions, beatings, and other abuses carried out by Linyi population planning officials.

- Encourage Chinese officials to permit greater public discussion and debate concerning population planning policies and to demonstrate greater responsiveness to public concerns. Impress upon China’s leaders the importance of promoting legal aid and training programs that help citizens pursue compensation and other remedies against the state for injury suffered as a result of official abuse related to China’s population planning policies. Provisions in China’s Law on State Compensation provide for such remedies for citizens subject to abuse and personal injury by administrative officials, including population planning officials. Provide funding and support for the development of programs and international cooperation in this area.

FREEDOM OF RESIDENCE

Findings

- China’s household registration (hukou) system remains as a foundation for discrimination and the violation of the rights of rural migrants in urban areas. In security preparations for the 2008 Beijing Summer Olympic Games, officials throughout the country intensified inspections of migrants’ hukou status. The rights of migrants without legal residency status were placed at increased risk, especially in urban areas where employment and social benefits are linked to hukou status.

- Recent hukou reforms have relaxed restrictions on citizens’ choice of permanent place of residence, but implementation at the local level has been uneven. Jiangsu and Yunnan provinces and Shenzhen city implemented major hukou reforms. Fiscal pressure associated with the provision of services to rising numbers of hukou holders prompted Zhuhai city to suspend its hukou application process.

Recommendations

- Initiate a program of U.S.-China bilateral cooperation that revives sister-city and sister-state/province exchanges as a vehicle for the discussion of ideas on migrant issues among local officials. Engage in international dialogue on migration and hukou reform to develop effective models for China’s reform efforts.

- Enlist the support of the business community in encouraging measures to equalize citizens’ ability to change their residence, and to eliminate outstanding rules that link hukou status to access to public services like healthcare and education. Recognize as good corporate citizens U.S. businesses in China with corporate social responsibility programs that address migrant issues in meaningful ways (e.g., awareness campaigns to eliminate discrimination against migrants and their children, and to reduce migrants’ vulnerability to exploitation).

LIBERTY OF MOVEMENT

Findings

- China strictly controlled citizens’ movement between the mainland and the special administrative regions (SAR) of Hong Kong and Macau. Officials used the granting and denial of "Home Return Permits" to limit access to the mainland by SAR-based pro-democracy activists.

- The use of extralegal house arrest to control or punish religious adherents, activists, or rights defenders deemed to act outside approved parameters intensified during the past year.

- Chinese authorities continued to use arbitrary restrictions on individual liberty of movement for retaliatory purposes. Authorities placed the family members of rights advocates under house arrest in retaliation for their advocacy activities.

- In the past year, authorities confiscated, revoked, denied entry, or refused to renew or accept the passport applications of several known dissidents.

Recommendations

- Call for China’s granting Home Return Permits to Hong Kong- and Macau-based Chinese advocates.

- In press statements, letters, and town hall meetings, spotlight the issue of arbitrary restrictions on individual liberty of movement, including limitations on Yuan Weijing and Zeng Jinyan, who have been under house arrest because of their spouses’ activism.

- Urge Chinese officials to consider passport renewals of dissidents and raise the issue of arbitrary denial of entry.

STATUS OF WOMEN

Findings

- Women continued to encounter gender-based discrimination, especially with respect to their exercise of land and property rights, and when attempting to access benefits associated with their village hukous (household registration). Chinese women, especially migrant, impoverished, and ethnic minority women, continue to be unaware of their legal options when their rights are violated.

- Coercive population planning policies remain in place in violation of internationally recognized human rights.

- This year marked the first time that a Chinese court mandated criminal punishment in a sexual harassment case. A Chinese court this year issued the first civil protection order in a divorce case involving domestic violence.

- Women have the right to vote and run in village committee elections, but continue to occupy a disproportionately low number of seats, Communist Party posts, government offices, and positions of significant power.

- Reliable statistical information and other data that are disaggregated by sex and region are insufficient, posing challenges for Chinese women’s rights advocacy organizations seeking to assess the effectiveness with which the Communist Party and government policies designed to help women are implemented.

Recommendations

- Initiate new bilateral exchanges between U.S. and Chinese law enforcement, judicial officials, and civil society organizations geared toward expanding comprehensive social services for women, including literacy programs that focus on combating illiteracy among women, longer-term options for sheltering domestic violence survivors, and psychological counseling and suicide prevention programs, especially in rural areas.

- Urge Chinese counterparts to support initiatives that help raise public awareness of women’s issues and rights, especially as they affect migrant women, women from rural communities, and ethnic minority women.

- Fund non-governmental organizations that provide training to independent Chinese groups that in turn train legal officials and social service providers in women’s issues and rights, work on domestic violence and sexual harassment issues, and that strengthen collection and publication of data on issues affecting women.

HUMAN TRAFFICKING

Findings

- The Chinese government lacks a comprehensive anti-trafficking policy to combat all forms of trafficking. The government’s definition of trafficking is narrow, and focuses on the abduction and selling of women and children. The National Plan of Action on Combating Trafficking in Women and Children (2008–2012), released in December 2007, neglects male adults, who are often targeted for forced labor.

- The Chinese government has not fulfilled its counter-trafficking-related international obligations, and has obstructed the independent operation of non-governmental and international organizations that offer assistance on trafficking issues.

- Incidents this year involving child labor in Guangdong province and forced labor in Heilongjiang reflect legal and administrative weaknesses in China’s anti-trafficking enforcement.

Recommendations

- Urge Chinese government officials to sign and ratify the Trafficking in Persons Protocol, to revise the government’s definition of trafficking and reform its anti-trafficking laws to align with international standards, and to abide by its international obligations with regard to North Korean refugees who become trafficking victims.

- Encourage Chinese embassy officials in the United States to better protect Chinese citizens who have been trafficked here by issuing the necessary travel documents and other documentation to trafficking victims in a timely manner.

- Fund research on trafficking-related issues in China, including the interplay between population planning policies, trafficking, and adoption.

- Support bilateral exchanges between U.S. and Chinese law enforcement officials and civil society organizations that work on trafficking.

NORTH KOREAN REFUGEES IN CHINA

Findings

- In the lead-up to the 2008 Beijing Summer Olympic Games, Chinese central and local authorities stepped up efforts to locate and forcibly repatriate North Korean refugees hiding in China. Border surveillance and crackdowns against refugees and the ethnic Korean citizens of China who harbored them intensified.

- Penalties for harboring North Korean refugees reportedly were increased, including higher fines. Searches by public security officials of the homes of ethnic Koreans living in villages and towns near the border intensified.

- The central government ordered provincial religious affairs bureaus to investigate religious communities for signs of involvement with foreign co-religionists. Churches in the Yanbian Korean Autonomous Prefecture in Jilin province that were found to have ties to South Koreans or other foreign nationals were shut down.

- Chinese local authorities near the border with North Korea continued to deny access to education and other public goods for the children of North Korean women married to Chinese citizens. Chinese government officials contravened guarantees under the PRC Nationality Law (Article 4) and Compulsory Education Law (Article 5) by refusing to register the children of these couples to their father’s hukou (household registration) without proof of the mother’s status.

Recommendations

- Establish a task force to examine and support the efforts of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees to gain unfettered access to North Korean refugees in China, and to recommend a strategy for creating incentives for China to honor its obligations under the 1951 UN Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol by desisting from the forced repatriation of North Korean refugees, and terminating the policy of automatically classifying all undocumented North Korean border crossers as "illegal economic migrants."

- Support U.S. Government legal cooperation funding with China to assist with the drafting of national refugee regulations that provide formal and transparent procedures for the review of North Korean claims to refugee status.

PUBLIC HEALTH

Findings

- China’s Minister of Health stated for the first time that all persons have the right to basic healthcare regardless of age, gender, occupation, economic status, or place of residence.

- The effectiveness of central government policies to combat the spread of HIV/AIDS remained limited by Chinese leaders’ concerns over uncontrolled citizen activism and foreign-affiliated non-governmental organizations.

- Discrimination against persons with Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) remained widespread.

- HBV carriers, many with the assistance of legal advocacy groups, brought employment discrimination lawsuits under anti-discrimination provisions in China’s new Employment Promotion Law that took effect this year. The first such case resulted in a court-ordered settlement and damage award.

- China’s first employment discrimination case involving mental depression resulted in a damage award and reinstatement of employment.

Recommendations

- Call on the Chinese government to ease restrictions on civil society groups and provide more support to U.S. organizations that address HIV/AIDS and HBV. A robust civil society is critical to achieving the government’s goal of prevention and treatment of HIV/AIDS and HBV.

- Urge Chinese officials to focus attention on effective implementation of the Employment Promotion Law and related regulations which prohibit discrimination against persons living with HIV/AIDS, HBV, and other illnesses in hiring and in the workplace.

ENVIRONMENT

Findings

- Experts encountered difficulties accessing information on pollutants and in charting Beijing’s progress toward achieving its environment-related Olympic bid commitments.

- The structure of incentives at the local level in China does not encourage action in favor of greater environmental protection. Penalties for violations remain low, and enforcement capacity remains insufficient.

- As the central government issues legislative and regulatory measures aimed at reducing greenhouse gases, implementation and enforcement at the local level remains a challenge. According to a study released in October 2008 by the Chinese Academy of Sciences, China’s emissions of greenhouse gases could double in the next two decades.

- Concerns over environmental degradation and the government’s perceived lack of transparency and solicitation of public input have sparked protests in major urban centers. Environmental protesters in urban areas tended to organize protests through the Internet and other forms of electronic communication. Urban protests were relatively peaceful.

- Environmental protests in rural areas more frequently involved violent clashes with public security officers.

Recommendations

- Support technical assistance programs aimed at enhancing public participation in environmental impact hearings and improving the ability of environmental protection bureaus to respond to information requests from citizens under new open government information regulations.

- When arranging travel to China, request meetings with officials from the central government to discuss environmental governance best practices. In those meetings, emphasize the importance of enhancing the capacity and power of the Ministry of Environmental Protection (MEP) by providing it with more staff and resources and shifting control of local environmental protection bureaus from local governments to the MEP.

- Encourage bilateral and exchange programs to identify and catalogue the sources and amount of greenhouse gas emissions. Expand support for the U.S. EPA-China Environmental Law Initiative and for bilateral exchange programs relating to environmental protection and governance.

- Call attention to China’s practice of criminally punishing citizens who peacefully disseminate information relating to en-vironmental hazards and emergencies. Urge Chinese officials to release freelance writer Chen Daojun, who was detained on suspicion of "inciting splittism" under Article 103 of the Criminal Law, after he published an article on a foreign Web site calling for a halt in construction of a chemical plant near Chengdu, citing environmental concerns. Also urge Chinese officials to release other environmental activists including those whose cases are described in the Commission’s Political Prisoner Database.

- Encourage legal assistance programs aimed to create incentives for government and business to build partnerships that reduce greenhouse gas emissions by deploying renewable energy and developing next generation low carbon technologies. Encourage bilateral cooperation and exchange programs whereby both the United States and China work to develop a roadmap for reducing emissions that is acceptable to both developed and developing countries.

CIVIL SOCIETY

Findings

- There were 387,000 registered civil society organizations (CSOs) in China, including 3,259 legal aid organizations, by the end of 2007, up from 354,000 in 2006 and 154,000 in 2000.

- Chinese authorities strengthened control over civil society and non-governmental organizations (NGOs), especially in the run-up to the 2008 Beijing Summer Olympic Games.

- China has an urgent need for legal reform in the non-profit sector, including in the management and registration of NGOs, in the regulation of charitable activities and donations, and in the provision of social services to victims of human trafficking, forced labor, and natural disasters. These needs became more pronounced following the discovery last spring of another extensive forced labor network in Guangdong province, and after the May Sichuan earthquake.

- The Corporate Income Tax Law, effective on January 1, 2008, encourages public and corporate charitable donations through the provision of tax benefits. Corporate donations and support for NGO activities increased during this year.

Recommendations

- Facilitate dialogue and consultation among Chinese officials, NGOs, and rights advocates. Increase exchanges between NGO leaders from the United States and China, and bolster program funding to support civil society development and capacity building in China.

- Encourage U.S. companies operating in China to make in-kind pro bono contributions to the NGO sector (e.g., by reserving places for representatives of Chinese NGOs to participate free of charge in corporate training programs in China that provide organizational and management skills).

INSTITUTIONS OF DEMOCRATIC GOVERNANCE

Findings

- The direct election of government officials by non-Party members remained rare, the range of positions filled through elections narrow in scope and strictly confined to the local level, and mostly in villages.

- Some localities implemented a new pilot project called "open recommendations, direct elections." According to this model of local Party leadership election, the general public participates during the candidate nomination stage only. All local Party members—not just officials—may participate in the final casting of ballots.

- Local leaders in Shenzhen proposed making the city a "special political zone" for the trial of political reforms. The Shenzhen Municipal Party Committee approved a plan for electoral and governance reform.

- The 17th Party Congress in October 2007 failed to produce a sustained program of significant political reform. The Party Congress prepared for a likely leadership transition in 2012 and promoted ideas such as "scientific development" and "inner-party democracy."

Recommendations

- Support research on recent efforts in China’s Special Economic Zones to expand experimentation with democratic models of public participation in local policymaking.

- Press Chinese officials to revive and expand engagement with international NGOs specializing in election monitoring.

COMMERCIAL RULE OF LAW

Findings

- China continues to deviate in both law and practice from World Trade Organization (WTO) norms and other international economic norms. In a dispute concerning China’s legal and administrative measures affecting imports of auto parts, the WTO Dispute Resolution Body (DSB) ruled against China, in China’s first legal defeat since its accession to the WTO. In two WTO dispute cases brought against China by the United States and Mexico pertaining to Chinese export and import substitution subsidies prohibited by WTO rules, China agreed in settlements with both countries to eliminate the subsidies.

- China’s new Anti-Monopoly Law, which took effect in August 2008, may have a significant impact on the development of commercial rule of law in China, if it can be transparently and fairly implemented.

- China’s new National Intellectual Property Strategy does not fully specify plans to address well-documented deficiencies in China’s institutions for intellectual property rights (IPR) enforcement.

- Local governments in China are applying the rhetoric and tools of IPR protection to traditional knowledge possessed by China’s ethnic minority groups, but it remains unclear whether China’s legal and administrative institutions provide ways to accomplish this in a manner that protects the rights of ethnic minorities.

- A food safety crisis in September 2008 involving tainted milk powder illustrated the ineffectiveness of China’s "Special War" on product quality, declared in August 2007. China’s food safety and product quality problems do not stem from a failure to legislate on the issue, but rather from duplicative legislation and ineffective implementation.

- New Land Registration Measures implement China’s Property Law in part by addressing a deficiency in China’s "dual registration system" for land and buildings, and consolidating the registration of both land and buildings under a single local government entity.

Recommendations

- Convey to the Chinese government that international criticism of China continues because, in spite of what the Chinese government has written into its laws and regulations, China’s leaders in practice have failed to abide by their commitments, including commitments to WTO and other international economic norms, to worker rights, and to the free flow of information on which further development of the commercial rule of law depends.

- Convey to the Chinese government that rapid production of new legislation by itself is not a sign of progress. Rather, new and existing laws and regulations must be coupled with consistent, transparent, and effective implementation that meets international standards and protects individuals’ fundamental rights. Failure to do so risks undermining even well-intended law, no matter how well-crafted on paper, and diminishes not only the credibility of China’s stated commitments to reform but also the integrity of China’s legal and regulatory institutions. Convey to the Chinese government that China’s repeated failure to live up to its international commitments has seri-ously damaged its credibility.

- Convey to the Chinese government that its increasingly sig-nificant role in the international community also requires an increasing respect for and enforcement of its commitments to that community. Monitoring China’s compliance with its com-mitments to the international community is not meddling, but rather is in the interests of all members of the international community.

ACCESS TO JUSTICE

Findings

- The intimidation and harassment of lawyers by government and Party officials in China intensified during the past year. Lawyers were pressured not to take on politically sensitive cases, including the representation of Tibetans charged with crimes in connection with the March protests and parents seeking compensation for injuries their children sustained from drinking melamine-tainted milk. The authorities refused to renew the lawyers’ license of renowned human rights lawyer Teng Biao for his involvement in the effort to represent the Tibetans and his work on other human rights cases.

- Stronger Communist Party control over the judiciary was evident during this past year, reflected by the election as president of the Supreme People’s Court of Wang Shengjun, who rose to power through the public security and political-legal committee systems. President Hu Jintao instructed the courts, police, and procuratorates to uphold the "three supremes"—the Party’s cause, the people’s interests, and the Constitution and laws.

Recommendations

- Support funding for technical assistance programs on best practices in structuring independent lawyers’ associations and self-governance of the bar.

XINJIANG

Findings

- Human rights abuses in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR) remained severe, and repression increased in the past year. Authorities tightened repression amid preparations for the 2008 Beijing Summer Olympic Games, limited reports of terrorist and criminal activity, and protests among ethnic minorities.

- The Chinese government used anti-terrorism campaigns as a pretext for enforcing repressive security measures, especially among the ethnic Uyghur population, including wide-scale detentions, inspections of households, restrictions on Uyghurs’ domestic and international travel, restrictions on peaceful protest, and increased controls over religious activity and religious practitioners.

- Anti-terrorism and anti-crime campaigns have resulted in the imprisonment of Uyghurs for peaceful expressions of dissent, religious practice, and other non-violent activities.

- The government also continued to strengthen policies aimed at diluting Uyghur ethnic identity and promoting assimilation. Policies in areas such as language use, development, and migration have disadvantaged local ethnic minority residents and have positioned the XUAR to undergo broad cultural and demographic shifts in coming decades.

- In the past year, the Commission also observed continuing problems in the XUAR government’s treatment of civil society groups, labor policies, population planning practices, judicial capacity, and government policy toward Uyghur refugees and other individuals returned to China under the sway of China’s influence in other countries.

Recommendations

- Support legislation that expands U.S. Government resources for raising awareness of human rights conditions in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR) and for protecting Uyghur culture.

- Raise concern about conditions in the XUAR to Chinese officials and stress that protecting the rights of XUAR residents is a crucial step for securing true stability in the region. Condemn the use of the global war on terror as a pretext for suppressing human rights. Call for the release of citizens imprisoned for advocating ethnic minority rights or for their personal connection to rights advocates, including: Nurmemet Yasin (sentenced in 2005 to 10 years in prison after writing a short story); Abdulghani Memetemin (sentenced in 2003 to 20 years in prison for providing information on government repression to an overseas human rights organization); and Alim and Ablikim Abdureyim (adult children of activist Rebiya Kadeer, sentenced in 2006 and 2007 to 7 and 9 years in prison, respectively, for alleged economic and "secessionist" crimes); and other prisoners mentioned in this report and the Commission’s Political Prisoner Database.

- Support funding for non-governmental organizations that address human rights issues in the XUAR to enable them to continue to gather information on conditions in the region and develop programs to help Uyghurs increase their capacity to defend their rights and protect their culture, language, and heritage.

- Indicate to Chinese officials that Members of the U.S. Congress and Administration are aware that Chinese authorities themselves have called for improving conditions in the XUAR judiciary. Urge officials to take steps to address problems stemming from the lack of personnel proficient in ethnic minority languages. Call on rule of law programs that operate within China to devote resources to the training of legal personnel who are able to serve the legal needs of ethnic minority communities within the XUAR.

TIBET

Findings

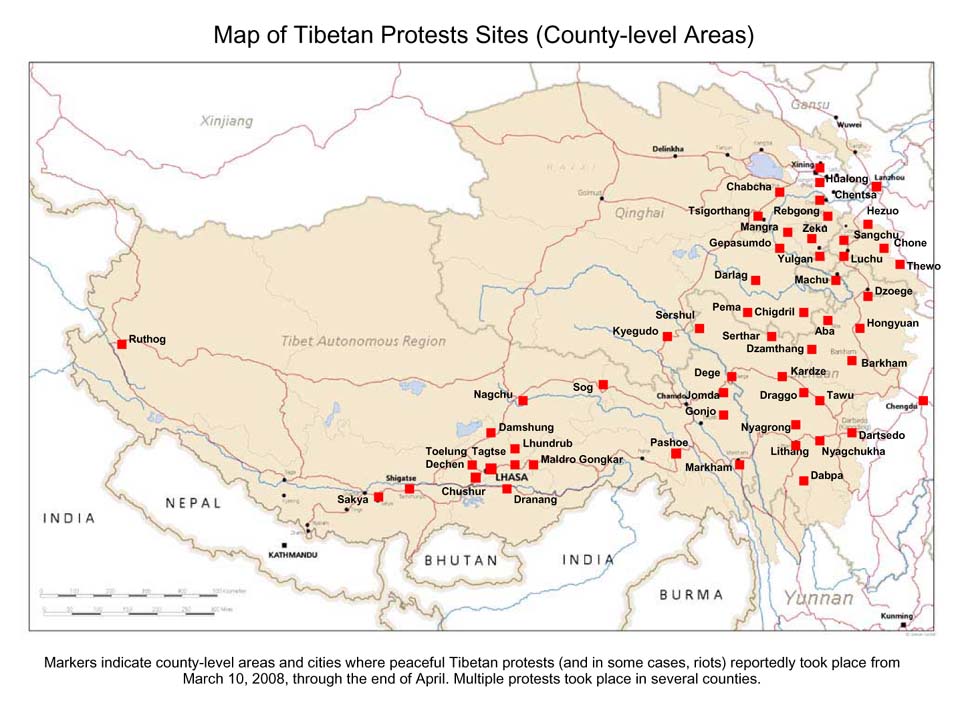

- As a result of the Chinese government crackdown on Tibetan communities, monasteries, nunneries, schools, and workplaces following the wave of Tibetan protests that began on March 10, 2008, Chinese government repression of Tibetans’ freedoms of speech, religion, and association has increased to what may be the highest level since approximately 1983, when Tibetans were able to set about reviving Tibetan Buddhist monasteries and nunneries.

- The status of the China-Dalai Lama dialogue deteriorated after the March 2008 protests and may require remedial measures before the dialogue can resume focus on its principal ob-jective—resolving the Tibet issue. China’s leadership blamed the Dalai Lama and "the Dalai Clique" for the Tibetan protests and rioting, and did not acknowledge the role of rising Tibetan frustration with Chinese policies that deprive Tibetans of rights and freedoms nominally protected under China’s Constitution and legal system. The Party hardened policy toward the Dalai Lama, increased attacks on the Dalai Lama’s legitimacy as a religious leader, and asserted that he is a criminal bent on splitting China.

- State repression of Tibetan Buddhism has reached its highest level since the Commission began to report on religious freedom for Tibetan Buddhists in 2002. Chinese government and Party policy toward Tibetan Buddhists’ practice of their religion played a central role in stoking frustration that resulted in the cascade of Tibetan protests that began on March 10, 2008. Reports have identified hundreds of Tibetan Buddhist monks and nuns whom security officials detained for participating in the protests, as well as members of Tibetan secular society who supported them.

- Chinese government interference with the norms of Tibetan Buddhism and unrelenting antagonism toward the Dalai Lama, one of the religion’s foremost teachers, serves to deepen division and distrust between Tibetan Buddhists and the government and Communist Party. The government seeks to use legal measures to remold Tibetan Buddhism to suit the state. Authorities in one Tibetan autonomous prefecture have announced unprecedented measures that seek to punish monks, nuns, religious teachers, and monastic officials accused of involvement in political protests in the prefecture.

- The Chinese government undermines the prospects for stability in the Tibetan autonomous areas of China by implementing economic development and educational policy in a manner that results in disadvantages for Tibetans. Weak implementation of the Regional Ethnic Autonomy Law has been a principal factor exacerbating Tibetan frustration by preventing Tibetans from using lawful means to protect their culture, language, and religion.

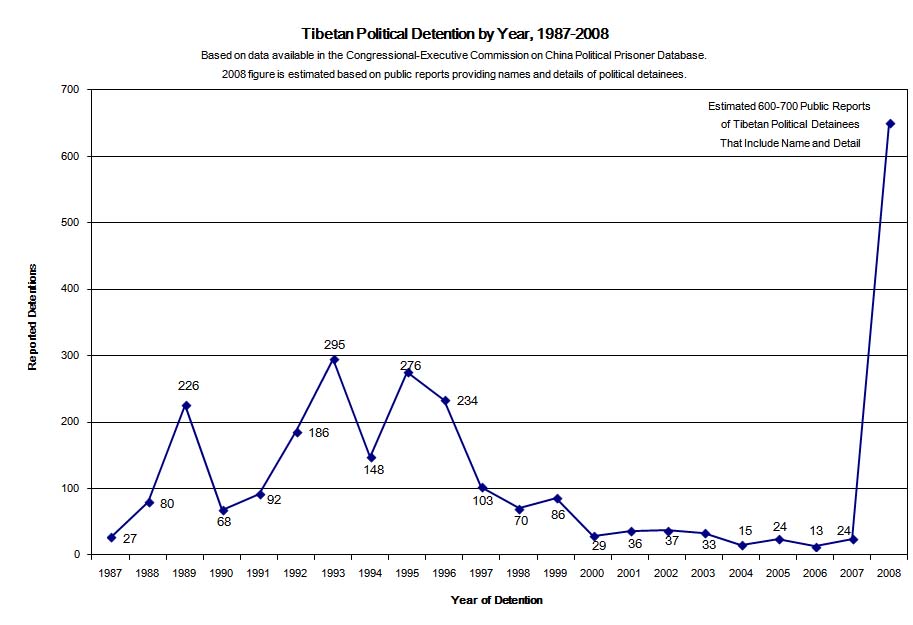

- At no time since Tibetans resumed political activism in 1987 has the magnitude and severity of consequences to Tibetans (named and unnamed) who protested against the Chinese government been as great as it is now upon the release of the Commission’s 2008 Annual Report. Unless Chinese authorities have released without charge a very high proportion of the Tibetans reportedly detained as a result of peaceful activity or expression on or after March 10, 2008, the resulting surge in the number of Tibetan political prisoners may prove to be the largest increase in such prisoners that has occurred under China’s current Constitution and Criminal Law.

Recommendations

Members of the U.S. Congress and Administration officials are encouraged to:

- Convey to the Chinese government the heightened importance and urgency of moving beyond the setback in dialogue with the Dalai Lama or his representatives following the March 2008 protests. A Chinese government decision to engage the Dalai Lama in substantive dialogue can result in a durable and mutually beneficial outcome for Chinese and Tibetans, and improve the outlook for local and regional security in the coming decades.

- Convey to the Chinese government, in light of the tragic consequences of the Tibetan protests and the continuing tension in Tibetan Buddhist institutions across the Tibetan plateau, the urgent importance of: reducing the level of state antagonism toward the Dalai Lama; ceasing aggressive campaigns of "patriotic education" that can result in further stress to local stability; respecting Tibetan Buddhists’ right to freedom of religion, including to identify and educate religious teachers in a manner consistent with their preferences and traditions; and using state powers such as passing laws and issuing regulations to protect the religious freedom of Tibetans instead of remolding Tibetan Buddhism to suit the state.

- Continue to urge the Chinese government to allow international observers to visit Gedun Choekyi Nyima, the Panchen Lama whom the Dalai Lama recognized, and his parents.

- In light of the heightened pressure on Tibetans and their communities following the March protests, increase funding for U.S. non-governmental organizations to develop programs that can assist Tibetans to increase their capacity to peacefully protect and develop their culture, language, and heritage; that can help to improve education, economic, and health conditions of ethnic Tibetans living in Tibetan areas of China; and that create sustainable benefits without encouraging an influx of non- Tibetans into these areas.

- Convey to the Chinese government the importance of distin-guishing between peaceful Tibetan protesters and rioters, honoring the Chinese Constitution’s reference to the freedoms of speech and association, and not treating peaceful protest as a crime. Request that the Chinese government provide details about Tibetans detained or charged with protest-related crimes, including: each person’s name; the charges (if any) against each person; the name and location of the prosecuting office ("procuratorate") and court handling each case; the availability of legal counsel to each defendant; and the name of each facility where such persons are detained or imprisoned. Request that Chinese authorities allow access by diplomats and other international observers to the trials of such persons.

- Continue to raise in meetings and correspondence with Chinese officials the cases of Tibetans who are imprisoned as punishment for the peaceful exercise of human rights. Representative examples include: former Tibetan monk Jigme Gyatso (now serving an extended 18-year sentence for printing leaflets, distributing posters, and later shouting pro-Dalai Lama slogans in prison); monk Choeying Khedrub (sentenced to life imprisonment for printing leaflets); reincarnated lama Bangri Chogtrul (serving a sentence of 18 years commuted from life imprisonment for "inciting splittism"); and nomad Ronggyal Adrag (sentenced to 8 years’ imprisonment for shout-ing political slogans at a public festival).

- The United States should continue to seek a consulate in Lhasa in order to provide services to Americans in Western China. With the closest consulate in Chengdu, a 1,500 mile bus ride from the Tibetan capital of Lhasa, American travelers are largely without assistance in Western China. This was recently underscored during unrest in Lhasa when U.S. citizens could not get out and American diplomats could not enter the Tibetan Autonomous Region.

The Commission adopted this report by a vote of 22 to 1.†

POLITICAL PRISONER DATABASE

Recommendations

When composing correspondence advocating on behalf of a political or religious prisoner, or preparing for official travel to China, Members of Congress and Administration officials are encouraged to:

- Check the Political Prisoner Database (PPD) (https://ppd.cecc.gov) for reliable, up-to-date information on one prisoner, or on groups of prisoners. Consult a prisoner’s database record for more detailed information about the prisoner’s case, including his or her alleged crime, specific human rights that officials have violated, stage in the legal process, and location of detention or imprisonment, if known.

- Advise official and private delegations traveling to China to present Chinese officials with lists of political and religious prisoners compiled from database records.

- Urge U.S. state and local officials and private citizens involved in sister-state and sister-city relationships with China to explore the database, and to advocate for the release of political and religious prisoners in China.

A POWERFUL RESOURCE FOR ADVOCACY

The Commission’s Annual Report provides information about Chinese political and religious prisoners1 in the context of specific human rights and rule of law abuses. Many of the abuses result from the Chinese Communist Party and government’s application of policies and laws. The Commission relies on the Political Prisoner Database (PPD), a publicly available online database maintained by the Commission, for its own advocacy and research work, including the preparation of the Annual Report, and routinely uses the database to prepare summaries of information about political and religious prisoners for Members of Congress and Administration officials.

The Commission invites the public to read about issue-specific Chinese political imprisonment in sections of this Annual Report, and to access and make use of the PPD at https://ppd.cecc.gov. (Information on how to use the PPD is available at: https:// www.cecc.gov/pages/victims/index.php.)

The PPD has served, since its launch in November 2004, as a unique and powerful resource for governments, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), educational institutions, and individuals who research political and religious imprisonment in China, or that advocate on behalf of such prisoners. The most important feature of the PPD is that it is structured as a genuine database and uses a powerful query engine. Though completely Web-based, it is not an archive that uses a simple or advanced search tool, nor is it a library of Web pages and files.

The PPD received approximately 23,000 online requests for prisoner information during the 12-month period ending July 31, 2008. During the entire period of PPD operation beginning in late 2004, approximately 36 percent of the requests for information have originated from government (.gov) Internet domains, 17 percent from network (.net) domains, 10 percent from international domains, 8 percent from commercial (.com) domains, 2 percent from education (.edu) domains, and 2 percent from organization (.org) domains. Approximately 20 percent of the requests have been from numerical Internet addresses that do not provide information about the name of an organization or the type of domain.

POLITICAL PRISONERS

The PPD seeks to provide users with prisoner information that is reliable and up-to-date. Commission staff members work to maintain and update political prisoner records based on their areas of expertise. The staff seek to provide objective analysis of information about individual prisoners, and about events and trends that drive political and religious imprisonment in China.

As of October 31, 2008, the PPD contained information on 4,793 cases of political or religious imprisonment in China. Of those, 1,088 are cases of political and religious prisoners currently known or believed to be detained or imprisoned, and 3,705 are cases of prisoners who are known or believed to have been released, executed or to have escaped. The Commission notes that there are considerably more than 1,088 cases of current political and religious imprisonment in China. The Commission staff works on an ongoing basis to add cases of political and religious imprisonment to the PPD.

During 2008, the Commission for the first time published a series of lists of current religious and political prisoners. The number of prisoners rose unusually steeply from list to list, principally as a result of the Commission’s ongoing work creating new case records for the large number of Tibetan protesters detained from March 2008 onward. On June 26, 2008, the Commission published a list of 734 current religious and political prisoners in China.2 On August 7, 2008, the Commission posted on its Web site a list of 920 political prisoners currently known or believed to be detained or imprisoned in China. The August 7 PPD list was arranged in reverse chronological order by date of detention, placing the most recent detentions first and facilitating a review of detention and imprisonment in the months preceding the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games.

The Dui Hua Foundation, based in San Francisco, and the former Tibet Information Network, based in London, shared their extensive experience and data on political and religious prisoners in China with the Commission to help establish the database.3 The Dui Hua Foundation continues to do so. The Commission also relies on its own staff research for prisoner information, as well as on information provided by NGOs, other groups that specialize in promoting human rights and opposing political and religious imprisonment, and other public sources of information.

DATABASE TECHNOLOGY

The PPD aims to provide a technology with sufficient power to cope with the scope and complexity of political imprisonment in China. The first component of an upgrade to the database will be available for public use before the end of 2008 and additional upgrade components will be available in 2009. The upgrade will leverage the capacity of the Commission’s information and technology resources to support research, reporting, and advocacy by the U.S. Congress and Administration, and by the public, on behalf of political and religious prisoners in China.

Upgrading the Database To Leverage Impact

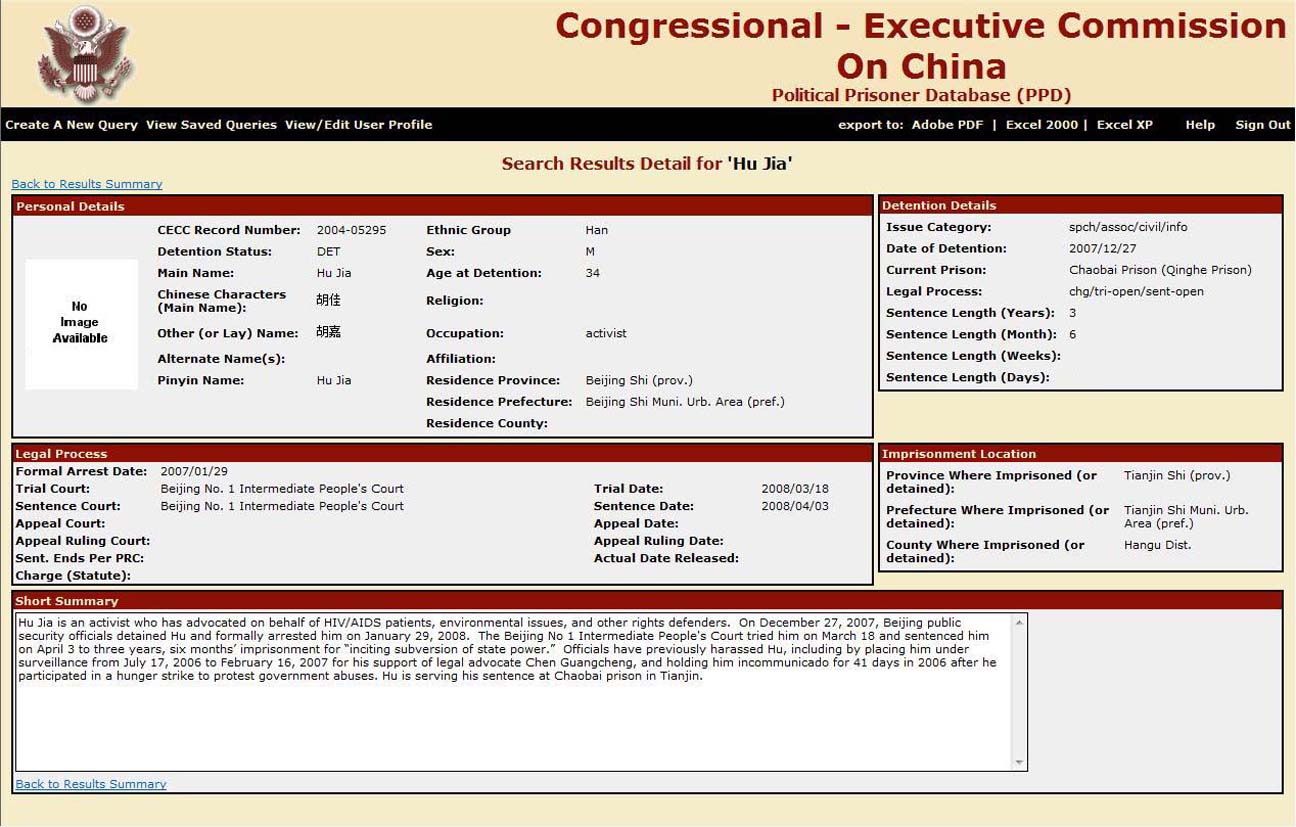

The Commission began work to upgrade the PPD soon after publication of the 2007 Annual Report. The component of the upgrade that will be available for public use before the end of 2008 will increase the number of types of information available from 19 to 40. The upgrade will allow users to query for and retrieve information such as the names and locations of the courts that convicted political and religious prisoners, and the dates of key events in the legal process such as sentencing and decision upon appeal. The users will be able to download PPD information as Microsoft Excel or Adobe PDF files more easily—whether for a single prisoner record, a group of records that satisfies a user’s query, or all of the records available in the database. [See image, "CECC PPD: Sample Appearance of a Record Summary Page After Forthcoming Upgrade," below.]

Many records contain a short summary of the case that includes basic details about the political or religious imprisonment and the legal process leading to imprisonment. The upgrade will increase the length of the short summary about a prisoner and enable the PPD to provide Web links in a short summary that can open reports, articles, and texts of laws that are available on the Commission’s Web site or on other Web sites. Web links in Commission reports and articles will be able to open a prisoner’s PPD record.

Powerful Queries Provide Useful Responses

Each prisoner’s record describes the type of human rights violation by Chinese authorities that led to his or her detention. These include violations of the right to peaceful assembly, freedom of religion, freedom of association, and free expression, including the freedom to advocate peaceful social or political change and to criticize government policy or government officials. Users may search for prisoners by name, using either the Latin alphabet or Chinese characters. The PPD allows users to construct queries that include one or more types of data, including personal information or information about imprisonment. [See box, "Tutorial: How to Use the Commission’s Political Prisoner Database," below.]

Providing Information to Users While Respecting Their Privacy