CECC Special Topic Paper: Tibet 2008 - 2009

Introduction: Tibetans Persist With Protest, Government Strengthens Unpopular Policies

Government Shifts Toward More Aggressive International Policy on Tibet Issue

Status of Negotiations Between the Chinese Government and the Dalai Lama or His Representatives

Religious Freedom for Tibetan Buddhists: Tightening Control Over Tibetan Buddhism, Tibetan Buddhists

Tibetan Development Initiatives Reinforce Government Priorities: Focus on 2020

For Tibetans, Another Year of Heightened Security, Repression, Isolation

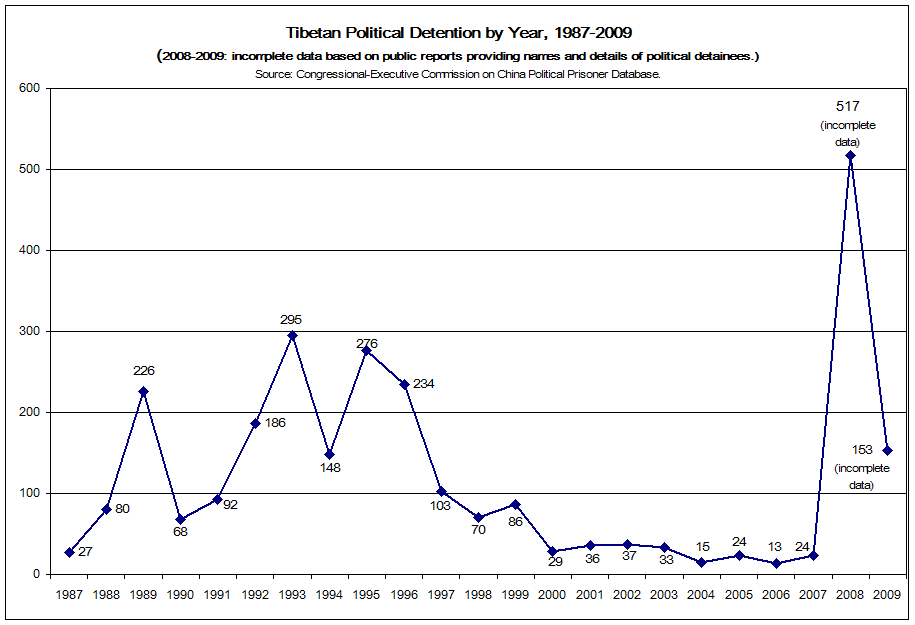

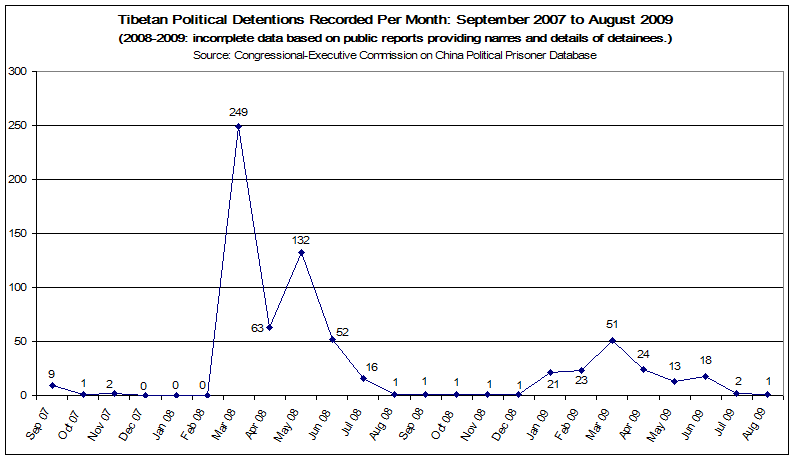

Political Detention and Imprisonment of Tibetans

Findings

- During the Commission’s 2009 Annual Report period, the Chinese government and Communist Party strengthened the policies and measures that frustrated Tibetans prior to the wave of Tibetan protests that started in March 2008. Tibetans continued to express their rejection of Chinese policies by means that included staging political protests. As a result of Chinese government and Party policy and implementation, and official campaigns to “educate” Tibetans about their obligations to conform to policy and law that many Tibetans believe harm their cultural identity and heritage, the level of repression of Tibetans’ freedoms of speech, religion, assembly, and association increased further.

- The environment for the dialogue between the Dalai Lama’s representatives and Chinese government and Party officials continued to deteriorate: both sides have referred to the dialogue as having stalled. The principal results of the eighth round of formal dialogue between the Dalai Lama’s representatives and Party officials were the Dalai Lama’s envoys’ handover of a detailed memorandum explaining Tibetan proposals for “genuine autonomy,” the Party’s rejection of the memorandum, and the Party’s continued insistence that the Dalai Lama fulfill additional preconditions on dialogue. The Memorandum’s focus on existing areas of Tibetan autonomy already established by the Chinese government could provide an incentive for Chinese officials to resume the dialogue.

- The government has in the past year used institutional, educational, legal, and propaganda channels to pressure Tibetan Buddhists to modify their religious views and aspirations. Chinese officials adopted a more assertive tone in expressing determination to select the next Dalai Lama, and to pressure Tibetans living in China to accept only a Dalai Lama approved by the Chinese government. Escalating government efforts to discredit the Dalai Lama and to transform Tibetan Buddhism into a doctrine that promotes government positions and policy has resulted instead in continuing Tibetan demands for freedom of religion and the Dalai Lama’s return to Tibet.

- The government pressed forward with a Party-led development policy that prioritizes infrastructure construction and casts Tibetan support for the Dalai Lama as the chief obstacle to Tibetan development. The government announced a major new infrastructure program—the “redesign” of Lhasa—that is scheduled for completion in 2020, the same year that the government plans to have ready for operation several new railways traversing sections of the Tibetan plateau. The TAR Communist Party and the Minister of Railways discussed in May 2009 accelerating the construction of railways that will access the TAR. In August 2009, China’s state-run media announced that work would begin on the Sichuan-Tibet railway would begin. The potential scale of demographic, economic, and environmental impact that the Sichuan-Tibet railway could have on Tibetan autonomous areas of China may far surpass the impact of the Qinghai-Tibet railway, which began operation in July 2006. Confrontations between Tibetans and Chinese government and security officials resulted in 2009 when Tibetans protested against natural resource development projects.

- The government and Party crackdown on Tibetan communities, monasteries, nunneries, schools, and workplaces following the wave of Tibetan protests that began on March 10, 2008, continued during 2009. Security measures intensified in some Tibetan areas during a months-long period that bracketed a series of sensitive anniversaries and observances in February and March 2009. As a result of increased government security measures and harsh action against protesters, Tibetan political protests in 2009 were smaller and of briefer duration than protests of March and April 2008. The Commission’s Political Prisoner Database (PPD) contained as of September 2009 a total of 670 records of Tibetans detained on or after March 10, 2008—a figure certain to be incomplete—for exercising rights such as the freedoms of speech, religion, assembly, and association.

Introduction: Tibetans Persist With Protest, Government Strengthens Unpopular Policies

During the Commission’s 2009 reporting year, the Chinese government and Communist Party strengthened policies and measures that frustrated Tibetans prior to the wave of Tibetan protests that started in March 2008. Such policies and measures include: the refusal to engage the Dalai Lama in meaningful talks; amplifying the scope and hostility of the anti-Dalai campaign; increasing the repression and control of religious freedom for Tibetans; poor implementation of the PRC Regional Ethnic Autonomy Law; and strengthening economic development initiatives that will increase further the influx of non-Tibetans into the Tibetan autonomous areas of China (and in doing so, increase the pressure on the Tibetan culture and heritage).

The Chinese government continued to state that Chinese policies in Tibetan areas are a success and in the past year adopted a more assertive stance in pressuring other governments to abandon support of the Dalai Lama and instead to support the Chinese government position on Tibetan issues. The Chinese government, to a large extent, bases its positive representation of conditions in Tibetan areas on economic growth data, on selective comparisons between pre-19491 Tibet and post-1978 reform-era China, and on dismisses as baseless or “splittist” views and analysis that do not support Chinese government and Party positions.

Tibetans continued during this reporting year to express their rejection of Chinese policies by means that included staging political protests that typically called for the Dalai Lama’s return to Tibet and for Tibetan independence or freedom. The presence of additional security forces, including People’s Armed Police, in areas where Tibetan protests took place in spring 2008 may have succeeded at limiting Tibetan protests, but not at stopping them entirely. Government measures to prevent information about Tibetan protests and protesters from leaving China have hindered human rights monitoring organizations from providing an adequate account of protests and their consequences.

As a result of Chinese government and Party policy and implementation, and official campaigns to “educate” Tibetans about their obligations to conform to policy and law that many Tibetans believe harm their cultural identity and heritage, the level of repression of Tibetans’ freedoms of speech, religion, assembly, and association increased further.

Government Shifts Toward More Aggressive International Policy on Tibet Issue

Senior Chinese government and Communist Party leaders speaking during the Commission’s 2009 reporting year, along with articles published in China’s state-controlled media, show that the leadership has increased the importance it attaches to the Tibet issue.2 Statements and reports indicate that the Chinese government may seek to utilize economic leverage to pressure other governments to support the Chinese government’s positions on Tibet.3 Senior leadership figures, including Foreign Minister Yang Jiechi, deny that the Chinese government violates Tibetans’ human rights, and instead assert that the only valid issue regarding Tibet is China’s right to oppose separatism and promote stability.4 President Hu Jintao, on March 9 (the day prior to a politically sensitive Tibetan anniversary), called for a “Great Wall of stability” to combat separatism and safeguard national unity.5

State Councilor Dai Bingguo, speaking in December 2008 before the Brookings Institution about the 30th anniversary of the establishment of U.S.-China diplomatic relations, placed Tibet alongside Taiwan as one of China’s two “core interests:”

To realize greater growth of China-U.S. relations, the key link is to make sure we handle well issues involving each other’s core interests and maintain and develop the strategic underpinning of our cooperation. Taiwan and Tibet-related issues concern China’s core interests. The Chinese people have an unshakable determination to defend our core interests.6

Dai named U.S. cooperation with China on the Tibet issue as “the key link” in building bilateral U.S.-China relations—a bilateral relationship that has as its “most urgent item,” according to Dai, the imperative to “to strengthen macroeconomic and financial policy coordination and work together to address the international financial crisis.”7 In a January 2009 communiqué to commemorate the establishment of diplomatic relations, the People’s Republic of China Embassy in the U.S. listed Tibet as one of the “sensitive issues” facing the two countries.8 The communiqué advocated a relationship in which each country would “earnestly respect and accommodate each other’s core interests and major concerns, and properly handle such differences and sensitive issues such as trade imbalance, IPR [intellectual property rights] protection, Taiwan, Tibet, human rights, and freedom of religious belief.”9

Zhu Xiaoming, a former senior official in the Party’s United Front Work Department10 and currently the head of an official “think tank” at Beijing’s China Tibetology Research Center,11 in March 2009 characterized international support for the Dalai Lama as an impediment to prospects for global recovery from the global economic downturn. Maintaining stable development is China’s best way to help the world deal with the financial crisis, Zhu said.12 International actors that “exploit the question of Tibet” cause China to “undertake more responsibilities” that interfere with China’s ability to respond to the economic downturn, which in turn is harmful for the world.13

China’s state-run media published articles and opinions urging the Chinese leadership to press other governments to support the Chinese government position on Tibet if other governments wish to have China’s support on international issues (including on economic issues). A March 2009 People’s Daily opinion observed that as China rises, “the rest of the world” needs “greater cooperation with China.”14 Such cooperation will be “impossible,” the opinion said, unless “the West . . . develops an objective and unbiased stance on Tibet.”15 People’s Daily concluded that without a “correct understanding” of the Tibet issue, “it is impossible to advance cooperation with China in a sincere manner.”16 A March 2009 China Daily opinion advocated for the emergence of a “China doctrine” that would establish Tibet as a “core concern” for China.17 A norm of such a doctrine would be for all countries to deny entry to the Dalai Lama, the China Daily opinion said, citing a recommendation that Foreign Minister Yang Jiechi made in a March 7 press conference.18

A June 2009 article by an expert at a Chinese security policy think tank provided a specific example of how the Chinese government may expect its rising global influence to result in other countries accommodating Chinese policies on Tibetan issues. In an article that labeled the Tibet issue a “thorn in China-Europe ties,” Gao Zugui, director of the Center of Strategic Studies at the China Institute of Contemporary International Relations,19 said that a “sense of anxiety and crisis” is developing among “old developed European countries” that face “marginalization in global affairs” as China catches up with them.20 Gao observed, “The rise of China’s global influence” and the resultant increase in other countries “becoming appreciative of [China’s] policies” means that “the Dalai Lama clique and some international anti-China forces find the space for their anti-China activities to be shrinking.”21

A September 24, 2009, People’s Daily article linked one aspect of the U.S.-China economic relationship—Chinese government purchases of U.S. Treasury bonds22—to Chinese demands that the U.S. President not meet with the Dalai Lama and the U.S. government not permit the Dalai Lama to visit the United States.23 The People’s Daily article referred to China as the U.S.’s “biggest creditor”24 and focused on U.S. President Barack Obama’s decision to meet with the Dalai Lama late in 2009,25 after the President’s first visit to China,26 instead of during the Dalai Lama’s October 5 to 10 visit to Washington DC.27 Some media reports characterized the President’s decision as an effort to improve relations with China,28 a depiction that the White House and the Dalai Lama’s Special Envoy both rejected.29 The September 24 People’s Daily article claimed that President Obama “quietly postponed” the meeting with the Dalai Lama to help achieve what People’s Daily described as “the core goal” of the President’s trip to China: “to coax China to continue to lend money by buying [U.S.] Treasury bonds.”30 If the President “intends to achieve some gains [toward that goal],” People’s Daily said, he would need to maintain a “clean slate”31 and take additional measures to satisfy the Chinese government:

What China expects is not simply rescheduling a meeting with the monk trying for decades to split China by lobbying around and vilifying China with sheer lie, but an end to all the involvement and encouragement in any form which would embolden and boost the monk's political ambitions.32

The notion that international support for the Dalai Lama could expose China to the threat of breakup, a topic that stirs a sense of nationalism among the Chinese people, is unsupported by the issues that the Chinese government and state media identify.33 The premise that the Chinese government should adopt a more aggressive Tibet policy, and use economic and other leverage to pressure governments to assist China in preventing China’s breakup by denying the Dalai Lama entry into other countries, is flawed for at least two reasons. First, the Dalai Lama continues to state that he seeks genuine autonomy for Tibet, not independence. [See Status of Negotiations Between the Chinese Government and the Dalai Lama or His Representatives below.] Second, the governments of countries that the Chinese government accuses of accommodating pro-Tibetan independence sentiment by hosting the Dalai Lama have not challenged China’s sovereignty over the Tibetan autonomous areas of China34—they question government policy and implementation in those areas.35 The U.S. State Department Report on Tibet Negotiations, for example, observes that U.S. policy recognizes the Tibet Autonomous Region and other Tibetan autonomous areas are part of China and that such a policy is “consistent with the view of the international community.”36

An expert on Tibetan political history appearing before a Commission roundtable in March 2009 called attention to the apparent emergence of a more aggressive Chinese government international policy on Tibet:

China now seems to be willing to demand that other countries adhere to its position on Tibet at the risk of damaging their good relations with China. The financial crisis in the United States and other capitalist countries has also seemed to give China the impression that its own economic and political system is superior and that it can be more demanding in its international relations. The manifestation of this new attitude has been new demands that its critics cease their complaints about Tibet. Recent articles in the Chinese press have suggested that not only must other countries not criticize China about Tibet but they must revise their beliefs about the issue.37

This Commission topic paper adds to and further develops information and analysis provided in Section V—Tibet of the Commission’s 2009 Annual Report, and incorporates the information and analysis contained therein.

|

|---|

Beijing Think Tank Finds Chinese Government Policy Principally Responsible for the “3.14 Incident”As Chinese government officials moved more aggressively to press other governments to support the government’s positions on the Tibet issue, the Beijing-based think tank, Open Constitution Initiative (OCI, Gongmeng), released a May 2009 report that rejected the government’s core assertion about Tibetan protests and rioting in March 2008.38 The “3.14 incident”39 was not the exclusive result of external influence by the Dalai Lama and organizations that the Chinese government associates with him (i.e., “masterminded by the Dalai Lama’s clique”),40 but the result of domestic (“internal”) issues, OCI said.41 The report applied the term “3.14 incident” in a manner consistent with Chinese government, Communist Party, and state-run media use: a collective reference to the protests and rioting that began on March 14, 2008, in Lhasa city, Tibet Autonomous Region, and then spread to other locations.42 The OCI report, compiled by “a group of prominent Chinese lawyers and legal scholars,”43 based its analysis on an independent investigation in two locations in each of two Tibetan areas: Lhasa city and Naidong (Nedong) county in the central Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR); and Hezuo (Tsoe) city and Xiahe (Sangchu) county in Gannan (Kanlho) Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture in Gansu Province.44 (Commission staff has not seen reports of Tibetan protests or rioting in Naidong in March 2008.) The OCI report did not include research or analysis on the eastern Tibetan area that Tibetans know as “Kham,”45 which includes Ganzi TAP in Sichuan province—the most active prefectural-level area of Tibetan protest based on information available in the Commission’s Political Prisoner Database. [See Political Detention and Imprisonment of Tibetans—Tibetans in Ganzi TAP Dominate Reports of Peaceful Protest Activity below.] OCI expressed its findings in a manner that shows that the authors aimed for officials to review the document,46 and identified a number of policy-based factors:

The OCI report provided nine recommendations that appear to be directed to the Chinese government. The recommendations, summarized in the order that they appear, follow.48

A Tibet issue expert addressed a March 2009 Commission roundtable on the significance of what he identified as a powerful Tibetan “interest group,”51 and what the OCI report described as a “new aristocratic class.” OCI’s recommendation on reducing local official corruption and dereliction of duty focused principally on “the new aristocracy.”52 According to the Tibet issue expert:

Officials from the Beijing Civil Affairs Bureau shut OCI down on July 17, 2009, according to reports by international media organizations.54 Xu Zhiyong, one of OCI’s founders, said the government officials claimed that OCI was not registered as a non-governmental organization (NGO).55 According to Xu, OCI did not need registration as an NGO because it is a charity organization functioning under the properly licensed Gongmeng Company. Xu characterized the shutdown of OCI as “unreasonable” and said, “We’ll continue to be conscientious and help those who need help.”56 The Commission did not observe any media reports that directly attributed the shutdown of OCI to the organization’s report on the “3.14 incident.” [For more information on the legal research and aid organization OCI see the Commission’s 2009 Annual Report.] |

|---|

Status of Negotiations Between the Chinese Government and the Dalai Lama or His Representatives

The environment for the dialogue between the Dalai Lama’s representatives and Chinese government and Communist Party officials continued to deteriorate during the Commission’s 2009 reporting year. Chinese officials increased their efforts to shift the focus of the dialogue away from discussing with the Dalai Lama’s envoys measures to protect and preserve the Tibetan culture, religion, and language, and instead to focus on new preconditions on the dialogue that pressure the Dalai Lama to function as an active proponent of Chinese government and Party policies on Tibet-related issues. The Commission’s 2008 Annual Report observed that, following the Tibetan protests that began in Lhasa on March 10, 2008,57 and, by the end of March, had swept across much of the ethnic Tibetan areas of China,58 the dialogue deteriorated from a status characterized by lack of progress to one that may require remedial measures before the dialogue could resume a focus on resolving the Tibet issue.59 The outlook for dialogue continued to deteriorate as the dates of sensitive observances and anniversaries in February and March 2009 approached and passed. Chinese security forces maintained crackdowns, Tibetan frustration continued to increase,60 protests (generally peaceful)61 continued to occur, and Chinese public security officials and People’s Armed Police met Tibetan protesters with harsh measures. [See For Tibetans, Another Year of Heightened Security, Repression, Isolation below.]

U.S. government policy recognizes the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) and Tibetan autonomous prefectures and counties62 in other provinces to be a part of China.63 The U.S. State Department’s 2009 Report on Tibet Negotiations observed, “[The Dalai Lama] represents the views of the vast majority of Tibetans and his consistent advocacy of non-violence is an important principle for making progress toward resolution of ongoing tensions. China’s engagement with the Dalai Lama or his representatives to resolve problems facing Tibetans is in the interest of both the Chinese Government and the Tibetan people.”64 The Report on Tibet Negotiations stated:

The United States continues to believe that meaningful dialogue represents the best way to resolve tensions in Tibet. We are disappointed that, after seven years of talks, there have not been any concrete results. We are concerned that in 2008 the Chinese government increased its negative rhetoric about the Dalai Lama, increased repression in Tibetan areas, and further restricted religious freedoms. We continue to urge both sides to engage in substantive dialogue and hope to see a ninth dialogue round in the near future that will lead to positive movement on questions related to Tibetans’ lives and livelihoods.65

The China-Dalai Lama Dialogue Stalls

The principal results of the eighth round of formal dialogue between the Dalai Lama’s representatives and Communist Party officials were the Dalai Lama’s envoys’ handover of the “Memorandum on Genuine Autonomy for the Tibetan People”66 (Memorandum), the Party’s rejection of the Memorandum, and the Party’s continued insistence that the Dalai Lama fulfill additional preconditions on dialogue. The Dalai Lama and Party officials have referred to the dialogue as having stalled.67

The Eighth Round of Dialogue, Handing Over the Memorandum

The Dalai Lama’s Special Envoy Lodi Gyari and Envoy Kelsang Gyaltsen arrived in Beijing on October 30, 2008, for the eighth round of formal dialogue since such contacts resumed in 2002.68 The envoys returned to India69 on November 5 following official meetings in Beijing on November 4 and 5 with Du Qinglin, Head of the Communist Party United Front Work Department (UFWD)70 and Vice Chairman of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, UFWD Executive Deputy Head Zhu Weiqun, and UFWD Deputy Head Sita (Sithar).71 Prior to the meetings, officials escorted the envoys to the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region.72 Academics in Beijing “briefed [the envoys] on the laws, policies and practices concerning China’s regional ethnic autonomy system.”73

The Dalai Lama’s envoys handed over to UFWD officials a memorandum setting out general proposals to create “genuine autonomy for the Tibetan people.”74 The Memorandum states in its introduction that during the seventh round of dialogue in July 2008, Du Qinglin “invited suggestions from His Holiness the Dalai Lama for the stability and development of Tibet,” and Zhu Weiqun “further said they would like to hear our views on the degree or form of autonomy we are seeking as well as on all aspects of regional autonomy within the scope of the Constitution of the PRC.”75 The Memorandum “puts forth our position on genuine autonomy and how the specific needs of the Tibetan nationality for autonomy and self-government can be met through application of the principles on autonomy of the Constitution of the People’s Republic of China, as we understand them.”76

Party Officials Attack the Dalai Lama, Press Preconditions

The day after the Dalai Lama’s envoys returned to India, UFWD Head Du Qinglin said the Dalai Lama should “fundamentally correct his political proposals.”77 Du stated that “at no time under no circumstances” would China tolerate “the slightest wavering or deviation” on what Du characterized as the issue of “safeguarding national unification and territorial integrity.”78 “Tibet’s ‘independence’ will not do, ‘semi-independence’ will not do, and ‘independence in disguise’ will not do, either,” he said.79 “Any attempt to create ethnic secession or damage ethnic unity under the banner of ‘genuine ethnic autonomy’ is absolutely impermissible,” Du stated.80

Du reiterated at the eighth round of dialogue81 a demand that the Dalai Lama personally fulfill the “four no supports,”82 a set of preconditions on the dialogue that Du initially pressed the envoys to deliver to the Dalai Lama during the July 2008 seventh round of dialogue.83 The new preconditions attempt to hold the Dalai Lama personally accountable for Tibetan views and activities that he does not support and that contradict his policies and guidance84—such as campaigning for Tibetan independence and discussing the potential use of violence in such a campaign. The “four no supports” pressure the Dalai Lama to take on the role of an active proponent of Chinese government political objectives.85

UFWD Executive Deputy Head Zhu Weiqun at a November 2008 State Council Information Office (SCIO) press conference elaborated on the Chinese government’s rejection of the Memorandum.86 He accused “the secessionist clique” of seeking to weaken central government authority, reject National People’s Congress legislative authority, and revise the PRC Constitution in an attempt to “have the rights of an independent country.”87 Zhu accused the envoys of not having “minimum sincerity” because for more than 20 years Tibetans have sought the creation of what Zhu called a “Greater Tibetan Autonomous Region”—an objective Zhu described as “unrealistic and absolutely impossible.”88 Zhu reasserted the government’s refusal to discuss “the Tibet issue,” but he acknowledged government willingness to allow the Dalai Lama and “some of those by his side” to return to China if the Dalai Lama first fulfills a number of preconditions.89

Neither Chinese Officials Nor the Dalai Lama See Progress

Zhu said in the November 2008 SCIO press conference that the dialogue had made no progress and blamed the unsatisfactory result on the envoys’ proposal to create a unified area of Tibetan administration.90 In a December 2008 televised interview, Zhu repeated the accusation that the Dalai Lama sought to establish “Greater Tibet,” and sought to discredit the Memorandum’s rationale that a unified administrative area would help to safeguard “the cultural characteristics and religious faith of the Tibetan nationality.”91

In a March 2009 interview, Zhu stated that the eighth round of dialogue was “stuck in a very difficult position” and once again faulted the Dalai Lama and his envoys.92 Zhu emphasized what he said was their failure to “carry out their promise” to abide by the requirements of the “four no supports.”93 (The Dalai Lama’s Special Envoy rejected the demands during the seventh round of dialogue when UFWD officials introduced the demands.)94 In June 2009, Zhu told a group of international reporters that the Dalai Lama’s continuing effort to promote “greater autonomy” after the Chinese government rejected the notion showed that the Dalai Lama lacks “honesty” and seeks to “trick” the international public.95 Zhu suggested that the Dalai Lama should “reflect on his actions, stop violent separatist activities, and take the ‘road to patriotism.’”96

After the apparent collapse of the dialogue, senior Chinese government officials, including Premier Wen Jiabao, continued to claim that talks with the Dalai Lama are possible if the Dalai Lama renounces separatism.97 The Dalai Lama continued to state that he is not seeking independence, but that he seeks “genuine autonomy”98 (or “meaningful autonomy”)99 for the Tibetan people. “Unfortunately, the Chinese side has rejected our memorandum in its totality, branding our suggestions as an attempt at ‘semi-independence’ and ‘independence in disguise’ and, for that reason, unacceptable,” the Dalai Lama said in an address to the European Parliament in December 2008.100

During the Commission’s 2009 reporting year, the Dalai Lama expressed candidly his disappointment with the Chinese government and his concern about the prospects for the Tibetan culture and heritage. “Although my faith in the Chinese leadership with regard to Tibet is becoming thinner and thinner, my faith in the Chinese people remains unshaken,” he told European parliamentarians in December 2008.101 In a May 2009 interview, the Dalai Lama likened what he described as “the Tibetan nation, an ancient nation with a unique cultural heritage,” as “passing through something like a death sentence.”102

A Detailed Tibetan Memorandum on “Genuine Autonomy”

The “Memorandum on Genuine Autonomy for the Tibetan People”103 (Memorandum) is unprecedented in that:

- it is a document (publicly available) that the Dalai Lama’s envoys presented directly to Communist Party officials in an effort to advance the dialogue;

- it sets out on behalf of the Dalai Lama a more detailed explanation of Tibetan aspirations for “genuine autonomy” than has been available previously or is available in the Dalai Lama’s Middle Way Approach (MWA);104 and

- it sets out on behalf of the Dalai Lama an analysis of whether or not the PRC Constitution and Regional Ethnic Autonomy Law (REAL)105 can accommodate Tibetan aspirations for “genuine autonomy.”

Principal Features of the MemorandumThe Memorandum reflects and elaborates on the principles set out in the Dalai Lama’s Middle Way Approach (MWA).106 The Memorandum cites the MWA in its introductory paragraph: “The essence of the Middle Way Approach is to secure genuine autonomy for the Tibetan people within the scope of the Constitution of the PRC.” The Dalai Lama’s official Web site lists eight “important components” of the MWA.107 The first three are:

In addition to an introduction, the Memorandum contains a section on each of the following six topics:

|

|---|

Memorandum Addresses, Has Potential To Resolve, Question of Tibetan Territory

With respect to the meaning of “Tibet,” there have been two principal areas of disagreement between the Chinese government and the Dalai Lama and his envoys. One issue is the territory to be recognized as “Tibet“; the other issue is whether or not all of such territory should be unified into a single administrative area.

The Memorandum’s description of territory to be included in a single Tibetan administrative area appears to resolve the first of the two principal areas of divergence between the Chinese government and the Dalai Lama. The Memorandum states explicitly that a single Tibetan administrative area should comprise “all the areas currently designated by the PRC as Tibetan autonomous areas”122—rather than include “the three traditional provinces of Tibet,” as the Middle Way Approach states.123 The area of the “traditional provinces of Tibet”124 is about 100,000 square miles greater than the total area of the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) and the Tibetan autonomous prefectures and counties located in Qinghai, Gansu, Sichuan, and Yunnan provinces.125 Aside from pockets of long-term Tibetan settlement in Qinghai province,126 most of the additional 100,000 square miles is made up of autonomous prefectures and counties allocated to other ethnic groups,127 and none of it is an area of Tibetan autonomy. [See Map 1 below for the names and locations of the Tibetan autonomous areas of China.128 See Map 2 below for an indication of areas where “the three traditional provinces of Tibet” extend beyond the Tibetan autonomous areas of China.129 See Table 1 below for information on Tibetan and Han Chinese population in the Tibetan autonomous areas of China.]

After the envoys handed over the Memorandum and its description of Tibetan territory based on the Chinese government’s designation of areas of Tibetan autonomy, senior Chinese officials continued to accuse the Dalai Lama of trying to establish a “Greater Tibet.”130 For example, Minister of Foreign Affairs Yang Jiechi said in March 2009, “The Dalai Lama and his followers insist to establish the so-called ‘Greater Tibet’ on one quarter of the Chinese territory.”131 Yang used the issue of the Dalai Lama’s interest in Tibetan territory to call into question the Dalai Lama’s legitimacy as a religious figure.132

The Memorandum’s proposal to base discussion of territory on the Tibetan autonomous areas of China constitutes an important and unprecedented measure by the Dalai Lama and his representatives to mitigate a key area of disagreement between the two sides. The proposal would render as without basis the Chinese government’s long-standing assertion that the Dalai Lama seeks “one-quarter of China” as an area of Tibetan autonomy. The Memorandum’s focus on existing areas of Tibetan autonomy already established by the Chinese government could provide an incentive for Chinese officials to resume the dialogue. In addition, mitigation of a key aspect of dispute between the two sides could create an objective basis for officials of other governments to encourage their Chinese government counterparts to discuss with the Dalai Lama or his representatives opportunities to achieve mutual benefit and take action to realize such benefits.

If, under the terms of the Memorandum, the Dalai Lama and his envoys seek to discuss unification only of areas the Chinese government has already designated as Tibetan autonomous, then the remaining issue is whether or not a change of such magnitude is possible to China’s administrative geography. The resulting single area of Tibetan autonomy would include the entire TAR, approximately 97 percent of Qinghai province,133 52 percent of Sichuan province,134 11 percent of Gansu province,135 and 6 percent of Yunnan province.136

Such changes to China’s map could face formidable opposition, but they are possible in principle under the PRC Constitution and Regional Ethnic Autonomy Law (REAL). The PRC Constitution authorizes establishing and changing areas of administrative geography with the approval of the National People’s Congress or the State Council, or both.137 The Constitution provides no role for provincial-level people’s congresses or governments in establishing or changing areas of administrative geography above the level of towns and townships.138 The REAL’s requirements are vague (“an autonomous area may not be revoked or merged without proper legal procedures”) and require higher- and lower-level state agencies affected by the change to agree to it (“thoroughly consult and formulate an agreement to submit for approval”).139

At a March 2009 Commission roundtable, three experts on the Tibet issue responded to a question on whether or not the Memorandum’s focus on areas China has already designated as Tibetan autonomous would advance the dialogue and help to reduce Chinese government insistence that the Dalai Lama is a “splittist.” None of the experts believed the change would result in a positive response from the government.140

Table 1: Tibetan Autonomous Areas of China—Tibetan and Han Chinese Population in 2000Based on Chinese Government 2000 Census Data | ||||

| Tibetan autonomous areas of China | Total | Tibetan | Han | Other |

| Tibet Autonomous Region (provincial-level) | 2,616,329 | (92.7%) 2,427,168 | 158,570 | 30,591 |

| Under Qinghai province administration | ||||

| Haibei (Tsojang) Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture | 258,922 | (24.1%) 62,520 | 94,841 | 101,561 |

| Hainan (Tsolho) Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture | 375,426 | (62.8%) 235,663 | 105,337 | 34,426 |

| Haixi (Tsonub) Mongol and Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture | 332,094 | (12.2%) 40,371 | 215,706 | 76,017 |

| Huangnan (Malho) Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture | 214,642 | (66.3%) 142,360 | 16,194 | 56,088 |

| Guoluo (Golog) Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture | 137,940 | (91.6%) 126,395 | 9,096 | 2,449 |

| Yushu (Yushul) Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture | 262,661 | (97.1%) 255,167 | 5,970 | 1,524 |

| Under Gansu province administration | ||||

| Gannan (Kanlho) Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture | 640,106 | (51.4%) 329,278 | 267,260 | 43,568 |

| Tianzhu (Pari) Tibetan Autonomous County (Wuwei Prefecture) | 221,347 | (29.9%) 66,125 | 139,190 | 16,032 |

| Under Sichuan province administration | ||||

| Ganzi (Kardze) Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture | 897,239 | (78.4%) 703,168 | 163,648 | 30,423 |

| Aba (Ngaba) Tibetan and Qiang Autonomous Prefecture | 847,468 | (53.7%) 455,238 | 209,270 | 182,960 |

| Muli (Mili) Tibetan Autonomous County (Liangshan Yi Autonomous Prefecture) | 124,462 | (32.4%) 40,312 | 27,199 | 56,951 |

| Under Yunnan province administration | ||||

| Diqing (Dechen) Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture | 353,518 | (33.1%) 117,099 | 57,928 | 178,491 |

| TOTAL | 7,282,154 | (68.7%) 5,000,864 | 1,470,209 | 811,081 |

| Areas without Tibetan autonomy but with at least 5 percent Tibetan population | Total | Tibetan | Han | Other |

| Under Qinghai province administration | ||||

| Xining Municipality | 1,849,713 | (5.2%) 96,091 | 1,375,013 | 378,609 |

| Haidong Prefecture | 1,391,565 | (9.2%) 128,025 | 783,893 | 479,647 |

| Under Gansu province administration | ||||

| Su’nan Yugur Autonomous County (Zhangye prefecture) | 36,678 | (24.4%) 8,969 | 17,010 | 10,699 |

| Under Sichuan province administration | ||||

| Shimian county (Ya’an municipality) | 123,261 | (9.8%) 12,044 | 97,106 | 14,111 |

| Baoxing county (Ya’an municipality) | 56,137 | (8.7%) 4,889 | 51,182 | 66 |

| TOTAL | 3,457,354 | (7.2%) 250,018 | 2,324,204 | 883,132 |

| Source: Tabulation on Nationalities of 2000 Population Census of China, Department of Population, Social, Science and Technology Statistics, National Bureau of Statistics, and Department of Economic Development, State Ethnic Affairs Commission (Beijing: Ethnic Publishing House, September 2003), Tables 10-1, 10-4. | ||||

Memorandum’s Vision of Autonomy and China’s Hierarchy of People’s Congresses and Governments

The Memorandum, in a section on “The Nature and Structure of the Autonomy,” sets out the objective for Tibetans to exercise autonomous rights including the right to “create their own regional government and government institutions,” “legislate on all matters within the competencies of the region,” and to “execute and administer decisions autonomously.”141 The Memorandum acknowledges, however, that the PRC Constitution impedes the function of autonomy:

Although the needs of the Tibetans are broadly consistent with the principles on autonomy contained in the Constitution, as we have shown, their realisation is impeded because of the existence of a number of problems, which makes the implementation of those principles today difficult or ineffective.142

Provisions in the PRC Constitution pose formidable obstacles to the Memorandum’s vision of autonomy by creating a state hierarchy of people’s congresses,143 governments,144 courts,145 and procuratorates146 in which higher-level institutions supervise lower-level institutions. The PRC Constitution’s language establishes that autonomous regions, prefectures, and counties—irrespective of their autonomous status—are integrated into the state’s hierarchy and are subordinated to tiered supervision.147

United Front Work Department Executive Deputy Head Zhu Weiqun discussed in a November 2008 State Council Information Office (SCIO) interview his views on why the Chinese government considers the Memorandum’s concept of “genuine autonomy” to be inconsistent with the PRC Constitution and law.148 He stressed that in China the system of “regional national autonomy” subordinates ethnic autonomous areas to “the country’s unitary national structure,” unlike “certain countries’ federal and confederate systems.”149 A 2004 Harvard University study of autonomy in the Tibetan autonomous areas of China considered a compilation of 161 laws and regulations “concerning autonomy arrangements,” in the Tibetan autonomous areas of China and found that poor implementation negates the value of autonomy legislation and erodes the rule of law.150

The PRC Constitution and law present additional impediments to the Memorandum’s objective that the government of a Tibetan area of “genuine autonomy” should enjoy the right to “legislate on all matters within the competencies of the region.” The Constitution, for example, empowers only the National People’s Congress (NPC) and the NPC Standing Committee (NPCSC) to enact or amend “statutes.”151 People’s congresses at the provincial, prefectural, and county levels, therefore, cannot enact or amend a “statute.” The Constitution (Article 116) authorizes ethnic autonomous people’s congresses “to enact autonomy regulations and specific regulations” in light of local circumstances, but the standing committees of higher levels of people’s congresses must approve such regulations before they can enter into effect.152 The PRC Legislation Law, however, intrudes on the right of ethnic autonomous people’s congresses to enact regulations by reserving to the State Council the power to issue regulations (if the NPCSC specifically authorizes the State Council to do so).153 The Legislation Law, however, authorizes an autonomous people’s congress to enact a “self-governing regulation or a separate regulation” that must be approved by the standing committee of a higher-level people’s congress at least at the provincial level.154

The Regional Ethnic Autonomy Law155 (REAL), China’s principal legal instrument for managing the affairs of ethnic minorities,156 states that the REAL is formulated to accord with the PRC Constitution157—and as such, the REAL reflects the Constitution’s barriers to autonomy. The REAL places ethnic autonomous areas under the state hierarchy of people’s institutions and requires ethnic autonomous governments to “place the interests of the state as a whole above all else and actively fulfill all tasks assigned by state institutions at higher levels.”158 Provisions of the REAL subordinate ethnic autonomous people’s governments,159 courts,160 and procuratorates161 to higher-level institutions.

The REAL (Article 19), in accordance with the Constitution, empowers autonomous people’s congresses to enact “self-governing regulations” and “separate regulations” in light of local conditions,162 but the Legislation Law impinges on the authority of ethnic autonomous people’s congresses to enact regulations.163 The Legislation Law goes further by interfering with a provision of the REAL that enables an ethnic autonomous people’s government to apply to a higher-level state agency to alter or cancel the implementation of a “resolution, decision, order, or instruction” if it does not “suit the actual conditions in an ethnic autonomous area.”164 The Legislation Law explicitly bars ethnic autonomous governments from enacting any variance to the laws and regulations that matter the most: those that are “dedicated to matters concerning ethnic autonomous areas.”165

The Memorandum’s analysis points to “significant limitations” imposed on decisionmaking by ethnic autonomous governments166 and a lack of clarity on the division of authority between the central government and autonomous governments.167 At the same time, the Memorandum acknowledges that the PRC Constitution “recognizes the principle that organs of self-government make laws and policy decisions that address local needs and that these may be different from those adopted elsewhere, including by the Central Government.”

The Memorandum proposes that the “parameters and specifics” of “genuine autonomy” for Tibet, based on the “unique needs and conditions of the Tibetan people and region,” should be detailed in a set of regulations enacted under the authority of Article 116 of the Constitution and Article 19 of the REAL.168 The Legislation Law, however (as noted above), impinges on the authority of ethnic autonomous people’s congresses to enact such regulations. The Memorandum proposes that “if it is found to be more appropriate,” “a separate set of laws or regulations [should be] adopted for that purpose,” and specifically notes that Article 31 of the Constitution “provides the flexibility to adopt special laws to respond to unique situations such as the Tibetan one.”169

Article 31 is the PRC Constitution’s sole basis for establishing areas and systems of administration that are not integrated into the state hierarchy of people’s congresses, governments, courts, and procuratorates established under Chapter III of the Constitution.170 (The REAL, for example, reflects provisions in Chapter III, Section 6.) Article 31 provides for the establishment of “special administrative regions”171 (SARs) and requires that the “systems to be instituted” in SARs must be enacted into law by the NPC “in light of the specific conditions.”172

The language of Article 31 is brief, broad, places no restrictions on the state’s application of the article, and has already served as a constitutional tool for creating alternative models of governance. Article 31 contains only one expression of restraint with respect to the establishment of SARs: the state should do so “when necessary.”173 The NPC so far has established two SARs under the provisions of Article 31: the Hong Kong SAR in 1990174 and the Macao SAR in 1993.175 The Chinese government established the Hong Kong and Macao SARs under the rubric of “one country, two systems” and as part of China’s campaign of “reunification of the motherland.”176

Chinese officials have stated that a level of administrative and political autonomy such as the NPC provided for Hong Kong and Macao under “one country, two systems” is inapplicable to the Tibetan areas in part simply because the Chinese government intends for autonomy under the REAL to be “different.” Zhu Weiqun, for example, said in his SCIO interview, “[R]egional national autonomy is an organic integration of national autonomy and regional autonomy—which is different from the ‘one country, two systems’ policy China implements in Hong Kong and Macao.”177 More to the point, the Preambles of the Basic Law of the Hong Kong and Macao SARs both indicate that a key feature of the “one country, two systems” is to set aside explicitly the system of communism: “Under the principle of ‘one country, two systems,’ the socialist system and policies will not be practiced” in the SARs.178

Chinese officials’ arguments that the principles of “one country, two systems” and “reunification of the motherland” do not apply to the Tibetan areas of China, and that Article 31 could not become the basis of a Tibetan solution, overlook the language of Article 31. Irrespective of the single purpose to which Article 31 has been so far applied, the article mentions neither “one country, two systems” nor “reunification of the motherland.”

Tibetans in Exile Meet, Decide To Maintain Support for the Middle Way Approach

On October 25, 2008, shortly before the Dalai Lama’s envoys arrived in China for the eighth round of dialogue, the Dalai Lama said in a Tibetan-language speech to Tibetans in India that his “faith and trust in the Chinese government is diminishing,” and that he could “see no useful purpose being served” by continuing his efforts to bear the responsibility for resolving the Tibet issue.179 “However,” he said, “if the Chinese leadership honestly engages in talks, then I may be in a position to take up this responsibility again. I will, then, sincerely engage with them.”180 He explained to the audience why (on September 11) he had requested “the Tibetan leadership” to convene a meeting to “thoroughly discuss” the views of the Tibetan public:181

The principal point . . . is that all the [Tibetan] people should take responsibility, should take a keen interest in the matter and should come up with the ways and means, as well as practicable actions, for the realisation of our cherished goal.182

The Tibetan government-in-exile (TGiE) announced on September 11 that the Dalai Lama had requested the TGiE to convene “a special general meeting to discuss the fundamental issues of Tibet.”183 The November 17 to 22 gathering in India included Tibetan political, religious, educational, cultural, and community leaders living outside of China in communities around the world.184 The Dalai Lama advised his envoys not to make any statements prior to the special meeting about discussions at the just-concluded eighth round of dialogue.185

Prior to the meeting, Tibetans speculated on whether or not Tibetans would continue to support the Dalai Lama’s Middle Way Approach (MWA). Tsewang Rigzin, President of the pro-independence Tibetan Youth Congress,186 said in a November 14, 2008, radio broadcast (that also included the Dalai Lama) that the MWA “hasn’t worked, it hasn’t borne any result, and we need to look at other options. . . . We look at independence as a solution.”187 Tsewang Rigzin expressed hope that the meeting would create an environment “where we can talk and put everything on the table what the future course of our struggle should be.”188 Participants in the meeting presented views supporting the MWA, independence, and self-determination.189

The TGiE published recommendations adopted by the meeting participants on November 22. Recommendations included urging the Dalai Lama “to continue to shoulder the responsibility of the spiritual and temporal leadership of the Tibetan struggle“; to continue support for the MWA; and to maintain non-violence irrespective of whether Tibetans pursue the MWA, self-determination, or independence.190

Religious Freedom for Tibetan Buddhists: Tightening Control Over Tibetan Buddhism, Tibetan Buddhists

Chinese government and Communist Party interference with the norms of Tibetan Buddhism and unremitting antagonism toward the Dalai Lama, key factors underlying the March 2008 eruption of Tibetan protest, continued to deepen Tibetan resentment and fuel additional Tibetan protests during the Commission’s 2009 reporting year. The government is taking measures to further increase government and Party influence over the teaching and practice of Tibetan Buddhism. The Party-led campaign to discredit the Dalai Lama as a religious leader and to prevent Tibetans from respecting him as such intensified. Statements by Chinese officials indicate that the government is ready to lead the selection of a successor to the Dalai Lama (now age 74) when he passes away, and that the government expects Tibetan Buddhists to embrace such a development.191

The government has in the past year used institutional, educational, legal, and propaganda channels to pressure Tibetan Buddhists to modify their religious views and aspirations. Escalating government efforts to discredit the Dalai Lama, Tibetan Buddhism’s leading teacher, and to transform the religion into a doctrine that promotes government positions and policy has resulted instead in continuing Tibetan demands for freedom of religion and the Dalai Lama’s return to Tibet.

Strengthened Efforts To Separate Tibetan Buddhists From the Dalai Lama

The Chinese government and Party have increased efforts to portray the Dalai Lama’s activity as an advocate on behalf of the Tibetan people and culture as a basis to deny him status as a religious figure. Seeking to end the Dalai Lama’s stature among Tibetans as a paramount religious leader is central to the government campaign to promote what it refers to as “stability” and “harmony” in the Tibetan areas of China.

Government, Party, Buddhist Association Leaders Challenge Dalai Lama’s Suitability as a Religious Figure

Senior Chinese officials and media organizations conducted an offensive against the Dalai Lama’s role as a religious leader and the right of Tibetan Buddhists to regard him as such during the period preceding a series of sensitive anniversaries and observances in February and March 2009.192 [See For Tibetans, Another Year of Heightened Security, Repression, Isolation—Rising Tension and a Crackdown as Sensitive Dates Approached, Passed below.] Minister of Foreign Affairs Yang Jiechi told a press conference in March that the Dalai Lama is “by no means a religious figure but a political figure.”193 A March People’s Daily editorial reasoned that expressing political views is incompatible with status as a religious figure: “‘Democracy,’ ‘government in exile,’ ‘new parliament,’ ‘Middle Way,’ ‘negotiation and talks,’ ‘actual progress’ . . . . All these expressions are baffling: how could a ‘religious leader’ have such explicit ‘political fervor’?”194

Jampa Phuntsog (Xiangba Pingcuo), Chairman of the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) government, asserted in March that the Chinese government and Communist Party as a matter of policy promote “religious harmony”—and accused the Dalai Lama of having “created disharmony among various religions and caused great confusion among the religious believers.”195 A senior TAR Party official in February 2009 referred to “the Dalai Clique” and advised a group of “patriotic, law-abiding, and advanced” Tibetan Buddhist monks and nuns that resisting “infiltrating and disrupting activities in monasteries and among the monks and nuns in the name of religion” is a prerequisite for “maintaining harmony and stability in the religious field.”196

The Buddhist Association of China (BAC), a “patriotic religious organization”197 established under Chinese government regulation198 and charged with serving as a “bridge” linking Buddhists to the Chinese government and the Communist Party,199 provided an example of the dependency of religious stature on political conformity when the BAC decided not to invite the Dalai Lama to the March 2009 “Second World Buddhist Forum.”200 The organizers chose the theme, “A Harmonious World, a Synergy of Conditions,” for the forum, convened in Wuxi city, Jiangsu province.201 BAC Vice President Ming Sheng described the Dalai Lama as a “political fugitive” and accused him of having done “lots of things to secede his motherland and go against his identity of being a Buddhist.”202 Ming reiterated government preconditions of the Dalai Lama and asserted that the Dalai Lama had yet to satisfy the demands.203 Instead of the Dalai Lama, Gyaltsen Norbu, installed by the government as the Panchen Lama in 1995204 after the government rejected the Dalai Lama’s recognition of Gedun Choekyi Nyima as the Panchen Lama,205 appeared at the forum.206

TAR Buddhist Association Uses Charter To Isolate Monks, Nuns From the Dalai Lama

The “Tibet Branch” (the TAR Branch) of the BAC (TBBAC) in February 2009 amended its charter to pressure Tibetan Buddhist monks and nuns to regard the Dalai Lama as a de facto criminal207 and a threat to Tibetan Buddhism, according to a report in China’s state-controlled media.208 The revised charter “urges” monks and nuns to “see clearly that the 14th Dalai Lama is the ringleader of the separatist political association which seeks ‘Tibet independence,’ a loyal tool of anti-China Western forces, the very root that causes social unrest in Tibet and the biggest obstacle for Tibetan Buddhism to build up its order.”209 Language characterizing the Dalai Lama as a “separatist” incorporated into the charter of a government-designated “religious organization” increases the risk of punishment for monks and nuns who maintain religious devotion to the Dalai Lama even if they do not engage in overt political activity.210

The TBBAC is bound under 2006 TAR government regulations to uphold government policy211 and accept government supervision and management.212 The same regulations authorize the TBBAC to establish Democratic Management Committees (DMCs, “management organizations”)213 within each TAR monastery and nunnery,214 and to establish provincial-level “measures” that determine how and whether a person may be officially “confirmed” as a monk or nun in a TAR monastery or nunnery.215

Government-Built Buddhist Academy Near Lhasa To Teach Politics Along With Religion

Officials announced in October 2008 the start of construction of the Tibet Autonomous Region’s (TAR) first “comprehensive higher educational institution of Tibetan Buddhism”216—a facility that will have the capacity to increase government supervision and standardization of Tibetan Buddhist education. A senior TAR Party official said on the day of the groundbreaking ceremony that the government-built facility217 “aims to train patriotic and devotional religious personnel who are widely recognized both in their religious accomplishments and moral character.”218 Instructors will also teach courses on non-religious subjects such as “politics and sociology,” the Party official said.219 The first phase of construction on the 43-acre campus, located in Qushui (Chushur) county, adjacent to Lhasa city, will include a library and buildings to accommodate “religious activities” and is scheduled to be completed in 2010.220

Patriotic and Legal Education: Seeking To Reshape Tibetan Buddhism

Chinese government and Communist Party officials continue to respond to Tibetan criticism of government policy and implementation—including on “freedom of religious belief”221— with aggressive campaigns of “patriotic education” (“love the country, love religion”)222 and legal education.223 Patriotic education sessions require monks and nuns to pass examinations on political texts, agree that Tibet is historically a part of China, accept the legitimacy of the Panchen Lama installed by the Chinese government, and denounce the Dalai Lama.”224 In June 2009, a monastic official who also holds the rank of Vice Chairman of the TAR Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC) spoke to monks at Jampaling (Qiangbalin) Monastery in Changdu (Chamdo) prefecture, TAR, and emphasized the dependency of “freedom of religion” on Party control and patriotism toward China.225 “Without the Party’s regulations,” he told the monks, “there would be no freedom of religion for the masses. To love religion, you must first love your country.”226

Officials justify such campaigns as legitimate and necessary state action by seeking to characterize (and conflate) a range of Tibetan objections to state policy into a purported threat to China’s unity and stability. For example, officials including Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) Party Secretary Zhang Qingli and Vice Minister of Public Security Zhang Xinfeng, speaking during a February 2009 teleconference on “the work of maintaining social stability,” called for “large numbers of party, government, military, and police personnel in Tibet to immediately go into action” and “resolutely smash the savage attacks by the Dalai clique and firmly win the current people’s war against separatism and for stability.”227 Principal speakers228 at the teleconference stressed the importance of education campaigns in achieving such objectives:

Party and government organizations at various levels, large numbers of cadres, and the broad masses of people in Tibet received profound education in patriotism and warning education in separatism in the blood-and-fire struggle against separatism, maintaining social stability and safeguarding the sanctity of the socialist legal system with their actual deeds.229

The Party and government do not limit the application of ideological education campaigns that allegedly protect China’s unity and stability to religious institutions. For example, a Party-run Web site reported in June 2009 that students at four TAR “institutes of higher education”230 would receive increased “ideological and political education.”231 Among the campaign goals were the creation of “a defensive ‘Great Wall of Steel,’” “increasing anti-separatist, political, and ideological resources available on the school websites, and ‘cleaning up’ and monitoring information on the internet.”232 The campaign would “aim to strengthen the opposition to the Dalai Clique’s separatist activities and create a solid educational foundation.”233 Each of the tertiary education institutions would conduct a speech contest with the theme, “Gratitude for progress, determination for success, give back to the community.”234

Intensive Period of Patriotic, Legal Education Aims for “New Order” in Tibetan Buddhism

The government and Party increased the use of intensive campaigns to “educate” monks and nuns after protests spread through the ethnic Tibetan areas of China in March to April 2008235 and maintained such campaigns during the Commission’s 2009 reporting year. A TAR Party official said on March 9, 2009, the day prior to a sensitive March 10th anniversary,236 that in the period since March 14, 2008, more than 2,300 officials had been dispatched to 505 TAR monasteries and nunneries237 to “promote the legal awareness of monks and nuns and dissuade them from being duped by separatist forces and ensure the normal practice of Buddhism.”238

Following the issuance of regulations on Tibetan Buddhism in 2006239 and 2007,240 Party and government officials have increased the emphasis on the use of legal measures and “legal education” to pressure Tibetan Buddhists into compliance with a state-defined “new order” for the religion. Lobsang Gyaltsen (Luosang Jianzan), a senior TAR Party and Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC) official, said in a February 2009 address, “Large numbers of patriotic monks and nuns should assist the government in strengthening the management of monasteries and religious affairs and improving monastic rules and religious discipline and contribute to building a new order in monasteries and religious activities.”241

Another senior TAR CPPCC official, Vice Chairman Pasang Dondrub (Basang Dunzhu), called on the Chinese government in March 2009 to further strengthen policies and legal measures that would bring the Tibetan Buddhist institution more firmly under state control and “shape behaviors of monks and nuns.”242 Pasang Dondrub offered a number of recommendations including the following:243

- “China should secure order of Tibetan Buddhism according to law to stem infiltration of ‘Tibet independence’ separatists.”

- “Monasteries and nunneries must strengthen their management by setting up or improving regulations, which should be used, along with Buddhism doctrines, to shape behaviors of monks and nuns.”

- “Nurture patriotism among the religious circle in Tibet and cultivate a team of personages who are ‘politically reliable, versed in Buddhism studies and morally admirable.’”

- “Law education for religion administrators should also be strengthened to enhance their understanding of the rule of law and their administration capability.”

Officials intend to conduct patriotic and legal education lectures at an unknown number of monastic institutions during the period surrounding October 1, 2009, the 60th anniversary of the Party’s establishment of the People’s Republic of China, according to a TAR official’s May 2009 remarks to Drepung Monastery monks.244 The official, Lobsang Dondrub (Luosang Dunzhu), Vice Chairman of the Standing Committee of the TAR People’s Congress and vice director of a “monastery work group,”245 reportedly told the monks to adhere to “Four Standards” set out by TAR Party Secretary Zhang Qingli. Lobsang Dondrub listed “four demands regarding peaceful monastery work”: (1) preserve national unity and oppose separatism; (2) build a long-term monastic management system to “resolve problems and eliminate the reactionary influence of the Dalai Clique;” (3) increase every monk’s “patriotic, legal, and political consciousness;” and (4) create a monastic implementation plan [for policy and regulations] that includes “organization of all the monks.”246 He told the monks that integrating socialism at the monastery would “ensure long-term stability.”247

Authorities Eject 1,200 Monks From Drepung, Sera; Detention, Education, Abuse Follow

Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) implementing measures issued in 2006248 for the Regulation on Religious Affairs249 may have played a role in authorities’ efforts to curtail and reverse the inter-provincial movement of monks seeking to study at other monasteries, especially at premier Tibetan Buddhist institutions, in the post-March 2008 period. Public security officials and monastic authorities in Drepung Monastery and Sera Monastery, both located in Lhasa city, sent back to their home provinces (mostly Qinghai, Gansu, and Sichuan) a total of at least 1,200 monks, according to an official March 2009 Chinese media report.250 Seven hundred of the monks were visiting251 Drepung and 500 were visiting Sera. Authorities investigating the alleged role of Drepung monks in March 14, 2008, rioting concluded that “most of the rioters were visiting monks,” the report said.252 Commission staff have not seen any Chinese government-published documentation supporting such a conclusion. The head of Drepung’s Democratic Management Committee (DMC) said that monks from elsewhere in the TAR and from other provinces “often spent years at the monastery,” and for the previous three years Drepung officials had not known the exact number of monks living at the monastery.253

The Drepung DMC assertion that monastery officials did not know how many monks were residing at Drepung as of March 2008 suggests that authorities may not have implemented fully TAR regulatory controls issued in 2006 on the movement of monks between the TAR and other provinces (and vice versa).254 One provision of the TAR 2006 measures includes a requirement that “religious personnel” from another province who wish to visit a TAR monastery or nunnery to study, or “religious personnel” from the TAR who wish to visit a monastery or nunnery in another province to study, must apply for and receive permission to do so from the provincial-level Religious Affairs Bureau (RAB) in the TAR and in the other province before undertaking travel.255 Requirements also apply to trans-prefectural travel in the TAR for the purpose of monastic study.256 Other provisions stipulate punishment for a monk or nun that can include revocation of status as “religious personnel” if a monk or nun does not fulfill requirements for traveling for the purpose of study.257 The Commission has not observed any reports indicating whether or not TAR authorities used the 2006 regulation as a legal basis for carrying out the expulsion of monks from Drepung and Sera.

The Chinese state-controlled media disclosure in March 2009 that officials ejected a total of 1,200 monks258 from Drepung and Sera in 2008 surpasses the figure of approximately 950 monks reported by an international media organization in August 2008.259 In addition, the official figure of 700 monks deported from Drepung to Qinghai province is greater than the figure of at least 600 monks reported by a non-governmental organization in March 2009.260 Authorities transferred 675 of the monks from Lhasa to Qinghai in late April 2008261 and held the monks in a “military detention center”262 guarded by People’s Armed Police263 near Golmud (Ge’ermu, Kermo) city in Haixi (Tsonub) Mongol and Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Qinghai province, where authorities forced the monks to participate in “rule of law education” classes.264 Another report described the classes as “patriotic education.”265 Authorities began returning the monks with Qinghai residency to their hometowns after three months of “education,”266 but it was late August 2008 before officials began to release monks with Sichuan province residency into the custody of government, Party, and public security officials from the monks’ home areas.267

In Golmud, authorities allegedly subjected the monks to “beatings and psychological torture,” according to a media organization report, and “many” monks suffered illness as a result.268 Few details are available about the current status or well-being of the 1,200 monks. A Western reporter encountered some of the monks at a Qinghai monastery in February 2009 and described them as among the most hostile toward Chinese government policy.269 The monks expressed frustration because they could not continue their monastic studies at Drepung and Sera, and resentment because officials sent 700 monks from Drepung to a camp in Golmud for “patriotic education,” according to the reporter.270

Official “Warns” Dalai Lama That Chinese Government Must Approve Next Dalai Lama

Chinese officials during the Commission’s 2009 reporting year adopted a more assertive tone in expressing determination to select the next Dalai Lama, and to pressure Tibetans living in China to accept only a Dalai Lama approved by the Chinese government. Remarks in March 2009 by Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) officials emphasized the government position that Tibetans will be permitted to regard as legitimate only a Dalai Lama approved by the government—as currently is the case for the Panchen Lama.271

Jampa Phuntsog (Xiangba Pingcuo), Chairman of the TAR government, “warned”272 the Dalai Lama not to interfere with what the Chinese government claims are “historical conventions and required religious rituals” that empower Chinese government and Party officials to supervise the selection of reincarnated Tibetan Buddhist teachers (“Living Buddhas”), according to a March 12, 2009, state-run media report.273 Legchog (Lieque), Chairman of the Standing Committee of the TAR People’s Congress, repeated the government claim that a “soul boy” (reincarnated teacher) must be approved by drawing lots from a golden urn “unless the central government agrees to exempt the ‘soul boy’ from the ritual.”274 The Chinese government claims such authority on the basis of a 17th century Qing dynasty edict that directed Tibetan religious leaders to identify reincarnations by drawing a name from an urn in the presence of an imperial Qing official.275 Tibetans used their own methods, however, to identify the current Dalai Lama and his predecessor.276

Jampa Phuntsog expressed confidence that Tibetan Buddhists living in China would not accept a (subsequent) Dalai Lama unless the Chinese government approves that Dalai Lama. “If the Dalai Lama does not follow the convention for political or other purposes,” he said, “I believe his reincarnation would not be acknowledged by religious people in Tibet, and the central government will never approve it.”277 The assertion that the government “will never approve” a Dalai Lama unless the government supervises the Dalai Lama’s selection would ensure that, under China’s current policy and law, a Tibetan Buddhist (in China) who regards an “unapproved” Dalai Lama as legitimate would be violating Chinese law—just as it currently is illegal for a Tibetan Buddhist (in China) to regard as legitimate Gedun Choekyi Nyima,278 the Panchen Lama whom the Dalai Lama recognized in 1995.279 Chinese security officials and courts have treated expressions of devotion toward Gedun Choekyi Nyima as “splittism” (a crime under Article 103 of the Criminal Law).280

The government took no publicly reported steps during the Commission’s 2009 reporting period to allow international observers to visit Gedun Choekyi Nyima,281 who turned 20 years of age in April 2009.282 Chinese officials have held Gedun Choekyi Nyima and his parents in incommunicado custody at unknown locations since May 1995.283

China’s Panchen Lama: Only the Party Can Lead Tibetans to a Bright Future

China’s leadership has increased the public role of 19-year-old284 Gyaltsen Norbu, installed as the 11th Panchen Lama by the State Council in December 1995.285 He represented Tibetan Buddhists at the March 2009 “Second World Buddhist Forum” in Wuxi city, Jiangsu province,286 and, speaking in English, told conference attendees that “China nowadays enjoys social harmony, stability and religious freedom.”287 Gyaltsen Norbu expressed his positive assessment on March 28,288 the first observance of “Serfs Emancipation Day,” at the peak of a period of heightened sensitivity and security crackdown in the Tibetan areas of China. [See For Tibetans, Another Year of Heightened Security, Repression, Isolation—Rising Tension and a Crackdown as Sensitive Dates Approached, Passed below.] China’s state-run media coverage of the Buddhist forum featured praise of Gyaltsen Norbu’s ability to address the forum in English, a strength that one conference attendee noted would allow him to “impress the world.”289 Gyaltsen Norbu, so far, has not denounced the Dalai Lama or challenged the Dalai Lama’s legitimacy as a religious leader, based on published reports on Gyaltsen Norbu’s remarks.290

Gyaltsen Norbu said in March 2009 that “Tibetan people could only achieve progress and have a bright future under the leadership of [the] Communist Party of China.”291 He expressed his intention to “inherit” the 10th Panchen Lama’s “tradition to be a patriot and try to maintain the nation’s unity, stability and harmony.”292 Gyaltsen Norbu’s reference refers to the 10th Panchen Lama (Lobsang Choekyi Gyaltsen),293 a figure whom Tibet issue advocates regard as a complex and skillful leader.294 On one hand, the 10th Panchen Lama served as a high-ranking official who worked closely with the Chinese government.295 On the other hand, he focused on protecting the Tibetan culture, language, and religion,296 wrote a critical assessment of Chinese government and Party policy in Tibetan areas,297 and delivered (five days before he died) a public speech questioning whether Chinese development policies had benefitted Tibetans.298

Tibetan Development Initiatives Reinforce Government Priorities: Focus on 2020

The Chinese government pressed forward during the Commission’s 2009 reporting year with a Communist Party-led development policy299 that prioritizes infrastructure construction and casts Tibetan support for the Dalai Lama as the chief obstacle to Tibetan development. The government, to a large extent, bases its positive representation of conditions in Tibetan areas on economic growth data,300 and on selective comparisons between pre-1949 Tibet301 and post-1978 reform-era China.302 The government announced a major new infrastructure program—the “redesign” of Lhasa—that is scheduled for completion in 2020, the same year that the government plans to have ready for operation several new railways traversing sections of the Tibetan plateau. Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) Communist Party Secretary Zhang Qingli and Minister of Railways Liu Zhijun held a forum in May 2009 on accelerating the construction of railways that will access the TAR.303

Party Labels Dalai Lama, “Dalai Clique” as Principal Obstructions to Development

The Chinese government and Communist Party conducted the anti-Dalai Lama campaign within the sphere of economic development, portraying in March 2009 the Dalai Lama and organizations that the government associates with the Dalai Lama as the chief obstruction to Tibetan development.304 Lhasa mayor Dorje Tsedrub (Duojie Cezhu) stated that “sabotage from the Dalai Lama group remains the biggest obstacle in the way of Tibet’s development,” and that “the violent riots on March 14 last year denied the autonomous region a good chance of development.”305 Legchog (Lieque), Chairman of the Standing Committee of the TAR People’s Congress, said in March 2009 that “the Dalai Lama group” is “not willing to see the stability and development in Tibet” and in 2009 had “intensified their secessionist activities.”306 In an April 2009 interview, Dorje Tsedrub widened the accusation of obstructing Tibetan development to include “international hostile forces.”307

Legchog, in his position as the TAR’s highest-ranking legislator, asserted in March 2009, “We can’t engage in construction amid an earthquake and pursue development in time of turmoil.”308 He blamed “the Dalai Clique” for “incessant sabotage,” and stated that “stability is the prerequisite for Tibet’s development.”309 The TAR People’s Congress would “strengthen legislation and law enforcement to fight separatism and ensure national security and regional stability,” he said.310 The Party-run Tibet Daily asserted in October 2008 that the TAR is unique in China because of “an extremely heavy task of promoting its economic and social development” as “the Dalai clique” seeks to create “disturbances and sabotages.”311 The article further stated that development would serve as “the foundation for resolving all problems in Tibet.”312

By characterizing the Dalai Lama as hostile to Tibetan development (as well as to national unity and stability, as explained above), the Party seeks to characterize the Dalai Lama as the principal threat to all three of the Party’s principal policy objectives in the Tibetan autonomous areas of China: unity, stability, and development. [See Commission Annual Reports in 2004,313 2005,314 2006,315 2007,316 and 2008317 for more information on Chinese government development policy in the Tibetan autonomous areas of China.]

Maintaining the Priority of Infrastructure Construction

The Communist Party and Chinese government continue to prioritize development policies that Tibetans resent and that many Tibetans (including the Dalai Lama) believe threaten the Tibetan culture and environment. The Dalai Lama said in his March 10, 2009, address to Tibetans,318 “Many infrastructural developments such as roads, airports, railways, and so forth, which seem to have brought progress to Tibetan areas, were really done with the political objective of sinicising Tibet at the huge cost of devastating the Tibetan environment and way of life.”319 The result, the Dalai Lama said, is that, “Today, the religion, culture, language and identity, which successive generations of Tibetans have considered more precious than their lives, are nearing extinction . . .”320

Lhasa Redesign To Feature “Old” and “New” Downtowns by 2020