2010 Annual Report

Congressional-Executive Commission on China2010 ANNUAL REPORT

Table of Contents

Freedom of Residence and Movement

North Korean Refugees in China

Climate Change and the Environment

III. Development of the Rule of Law

Institutions of Democratic Governance

VI. Developments in Hong Kong and Macau

VII. Endnotes (incorporated into each section above)

The Congressional-Executive Commission on China, established by the U.S.-China Relations Act of 2000 as China prepared to enter the World Trade Organization, is mandated by law to monitor human rights, including worker rights, and the development of the rule of law in China. The Commission by mandate also maintains a database of information on political prisoners in China—individuals who have been imprisoned by the Chinese government for exercising their civil and political rights under China’s Constitution and laws or under China’s international human rights obligations. All of the Commission’s reporting and its Political Prisoner Database are available to the public online via the Commission’s Web site, www.cecc.gov.

Preface

The findings of this Annual Report make clear that human rights conditions in China over the last year have deteriorated. This has occurred against the backdrop of China’s accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001, and the Chinese government’s years of preparation for accession, which provided the impetus for many changes to Chinese law. Those changes, some of which have been significant, have yet to produce legal institutions in China that are consistently and reliably transparent, accessible, and predictable. This has had far-reaching implications for the protection of human rights and the development of the rule of law in China.

The Chinese people have achieved success on many fronts, for example in health, education, and in improved living standards for large segments of the population, and they are justifiably proud of their many successes. But the Chinese government now must lead in protecting fundamental freedoms and human rights, including the rights of workers, and in defending the integrity of China’s legal institutions with no less skill and commitment than it dis-played in implementing economic reforms that allowed the industriousness of the Chinese people to lift millions out of poverty.

Most importantly, the Chinese government must free its political prisoners, who include some of the country’s most capable and socially committed citizens—scholar and writer Liu Xiaobo, HIV/ AIDS advocate Hu Jia, prominent attorney Gao Zhisheng, journalist Gheyret Niyaz, Tibetan environmentalist Karma Samdrub, and many others named in this Annual Report and in the Commission’s Political Prisoner Database. By engaging rather than repressing human rights advocates, the Chinese government would unleash constructive forces in Chinese society that are poised to address the very social problems with which the government and Party now find themselves overburdened: corruption, poor working conditions, occupational safety and health, environmental degradation, and police abuse among them.

Stability in China is in the national interest of the United States. The Chinese government’s full and firm commitment to openness, transparency, the rule of law, and the protection of human rights, including worker rights, marks a stability-preserving path forward for China. Anything less than the government’s full and firm commitment to protect and enforce these rights undermines stability in China.

Overview

Over the Commission’s 2010 reporting year, across the areas the Commission monitors, the following general themes emerged:

- New trends in political imprisonment include an increasingly harsh crackdown on lawyers and those who have a track record of human rights advocacy, particularly those who make use of the Internet and those from areas of the country the government deems to be politically sensitive (e.g., Tibetan areas and Xinjiang).

- Nexus between human rights and commercial rule of law, has become more evident particularly in connection with laws on state secrets, the Internet, and worker rights.

- Communist Party’s intolerance of independent sources of influence extends broadly across Chinese civil society, including with respect to organized labor.

- Chinese government’s new rhetoric on compliance with international human rights norms creates new challenges for U.S.-China dialogue and exchange.

- Global economic conditions have prompted the Chinese government to expand state economic and social control in a manner that impedes the development of the rule of law.

- Misapplication of law as a means of control has become more evident as the Communist Party has expanded and strengthened the capacity of law and regulation to serve as a means for the Party to control an increasing number of facets of daily life.

- Prospects for human rights and the rule of law in China depend on decisions taken at the highest levels of the Communist Party.

New Trends in Political Imprisonment

The Chinese government appears to be engaged in an increasingly harsh crackdown on lawyers and human rights defenders. The tightening of control over criminal lawyers, human rights lawyers, and the legal profession more generally has led some of China’s leading legal experts to state that the rule of law is in "full retreat" in China. Over the last two years, several lawyers involved in human rights advocacy work—including in legal cases involving house church members, public health advocates, Falun Gong practitioners, Tibetans, and others deemed by the government to threaten "social stability"—have been harassed and abused by the government based on who their clients are and the causes those clients represent.

The Internet appears to have given rise to a new category of political prisoners in China. Many citizens who criticize the government on blogs and comment boards face no severe repercussions— at most their comments may be deleted. But individuals who have a track record of human rights advocacy, political activism, grass-roots organizing, or opposition to the Communist Party, and some from areas of the country the government deems to be politically sensitive (e.g., Tibetan areas and Xinjiang), have been targeted systematically. Among the most common charges against these citizens are the crimes of "subverting state power" or "splittism," which carry a sentence of up to life imprisonment, and inciting subversion or "splittism," which carry a sentence of up to 15 years. Individuals, including lawyers, writers, scholars, and businesspeople, have been imprisoned on these charges for posting online essays critical of the government, for exposing corruption or environmental problems, or for trying to organize political opposition online, without advocating violence.

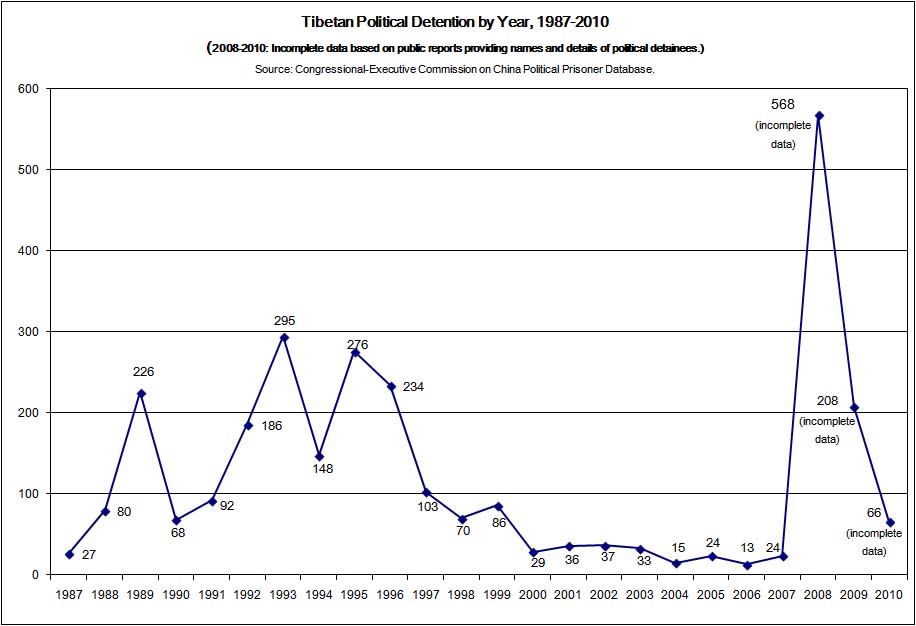

In the past year, government officials moved more aggressively to diminish or end the public influence of Tibetan civic and intellectual leaders, writers, and artists. Officials imprisoned such Tibetans in past years, but the frequency of using courts and the misapplication of criminal charges to remove such figures from society has increased. As of early September 2010, the Commission’s Political Prisoner Database had recorded more than 840 cases of political detention of Tibetans on or after March 10, 2008, when Tibetan protests began in Lhasa and then swept across the Tibetan plateau. The true number of political detentions during the period is certain to be far higher.

In the year since the government suppression of a demonstration by Uyghurs and multi-ethnic riots in Xinjiang starting July 5, 2009, human rights conditions in this far western region of China have worsened, and cases of political imprisonment remain of critical concern. At the same time that authorities have punished people for violent crimes committed in July 2009, they also have continued to conflate the right to demonstrate peacefully or to express criticism over government policy with criminal activity. In the past year, authorities imprisoned Uyghur Webmasters and a Uyghur journalist in connection with articles critical of conditions in Xinjiang and in connection with Internet postings calling for the July 2009 demonstrations. In the aftermath of the July 2009 events, authorities also carried out broad security sweeps resulting in mass detentions of Uyghur men and boys, some of whom appear to have had no connection to events in July 2009. The whereabouts of many people detained since July 2009 remain unknown.

Nexus Between Human Rights and Commercial Rule of Law

Developments over the past year have shown how business disputes and commercial issues can have real human rights implications when the Communist Party perceives its interests to be threatened. Under Chinese law, information relating to "national economic development" may be deemed a "state secret." Furthermore, officials sometimes deem information a state secret ex post facto, that is, after an alleged "crime" of unauthorized disclosure, trafficking, or possession of a "state secret" has occurred. Many Chinese companies dealing with foreign businesses are state-owned enterprises (SOEs) with close links to the government, heightening the possibility that such SOEs will press the government to classify commercial information as a state secret or that the government will use the charge of violating laws on state secrets to advantage Chinese commercial interests.

The crime of supplying a state secret to a foreign "organization" (a category that includes corporations) is punishable by up to life in prison. While it remains unclear whether this risk to foreign businesses has increased, high-profile cases in the last year illustrate that the risk remains real. Among such cases is that of Xue Feng, a geologist and U.S. citizen who helped his employer, an American firm, purchase commercially available information on oil wells and prospecting sites in China. The information was classified as a state secret after the purchase took place. A Chinese court then sentenced the geologist to eight years in prison. The case shows that the risk of being charged with violating laws on state secrets complicates the normal, legitimate gathering of commercial information. The imposition of such a risk whenever state ownership of industry is involved is contrary to standard international business practice and undermines the rule of law.

The controversy between the Chinese government and Google, Inc., over the last year highlighted the potential for Chinese censorship practices to interfere with the free flow of information among Chinese citizens and businesses, and between people and organizations in China and the rest of the world. The government appeared to single out Google in June 2009 during an anti-pornography campaign, saying Google was not doing enough to filter banned content (much of which is politically sensitive, not "pornographic"). In January 2010, Google announced that it had "detected a highly sophisticated and targeted attack on our corporate infrastructure originating from China" that it said had "resulted in the theft of intellectual property from Google." Google also said it had "evidence to suggest that a primary goal of the attackers was accessing the Gmail accounts of Chinese human rights activists." Google said that "[t]hese attacks and the surveillance they have uncovered—combined with attempts over the past year to further limit free speech on the web" led the company "to conclude that we should review the feasibility of our business operations in China." The Google controversy underscored what some business leaders have noted as the Chinese government’s long-growing impatience with private companies that it perceives to have grown too large or become too successful, or whose branding attracts too much loyalty outside of government-approved parameters.

The nexus between human rights and commercial rule of law also has been evident in the area of worker rights. High-profile worker actions during this reporting year included strikes calling for better wages and formal channels to submit grievances. In a number of strikes at prominent foreign manufacturing facilities in China, workers called for existing All-China Federation of Trade Unions (ACFTU)-affiliated unions to behave more independently within the confines of Chinese law. Striking workers’ demands for higher wages revealed that they may have been emboldened not only by protections for workers codified in labor laws that took effect in 2008, but also by a tighter labor market. However, they stopped short of calling for the formation of independent trade unions. The limited demands of workers reflected in part the political constraints imposed on the labor movement in China. Workers in China still are not guaranteed, either by law or in practice, full worker rights in accordance with international standards, including the right to organize into independent unions. The ACFTU, the official union under the direction of the Party, is the only legal trade union organization in China. All lower level unions must be affiliated with the ACFTU and must align with its overarching political concerns of maintaining "social stability" and economic growth.

Communist Party’s Intolerance of Independent Sources of Influence

The Communist Party’s determination to rein in independent sources of influence remained evident across Chinese society during this reporting year. For example, the Chinese government denies workers the right to organize into independent unions in part because the Party continues to regard organized labor as it does citizen activism in other spheres of public concern: as a threat to the Party’s hold on power and a potentially powerful competitor for allegiance. While legislative developments over the last three years now make collective bargaining a legal possibility in China, and efforts to develop collective labor contracting in some locales have progressed in limited respects (e.g., in Guangzhou and Shanghai), China’s leaders have made clear they will not tolerate an inde-pendent trade union movement. They do not see such a development as potentially helping to relieve the government of the burden of social pressures.

Chinese citizens who sought to establish and operate civil society organizations that focused on other issues deemed by officials to be "sensitive," including public health advocacy, housing rights advocacy, and advocacy on behalf of petitioners, ethnic minorities, or adherents of religious and spiritual groups, faced intimidation, har-assment, and punishment. The government continued to tighten its control over civil society groups through selective enforcement of regulations and through new regulations that make it difficult for some civil society organizations to accept tax deductible contributions or contributions from overseas donors.

The government also punished citizens who waged independent campaigns seeking greater government accountability. Activists who criticized the government for not doing enough to investigate the causes of school collapses in the May 2008 earthquake in Sichuan have been imprisoned. Tibetans engaged in environmental protection activities with Party and government encouragement found themselves facing imprisonment when their popularity soared and they criticized local officials for breaking laws that protect endangered animal species. Petitioners in many areas of China were mistreated, harassed, and detained for their involvement in advocating for housing rights and for organizing to protest forced evictions and relocations in which the government failed to meet its obligations to compensate residents fairly and in accordance with the law. Mistreatment of those advocating on behalf of individuals who suffered abuse at the hands of population planning officials continued.

Authorities also sought to tighten control over the Internet, the influence of which continues to grow, with more than 420 million users in China. Officials stepped up monitoring and control of blogging, news, video, and social networking sites; issued legal measures that could increase pressure on Internet companies to censor political content; and sought to impose greater legal requirements on those wishing to post or host content on the Internet that could lead to self-censorship of political content for fear of government retribution. The government also continued to quash attempts by Chinese media to test the boundaries of media independence, as illustrated, for example, when an editorial calling for reform of China’s household registration system jointly published in 13 newspapers was removed from the Internet, and one of its co-authors was forced to resign his position as editor of one of the papers.

A further example of the Chinese leadership’s determination to rein in independent sources of influence is the continuing ban on Falun Gong. Falun Gong is a spiritual movement established in China in the early 1990s based on Chinese meditative exercises called qigong. By 1999, the Falun Gong movement reportedly had grown to include an estimated 70 to 100 million followers (also called "practitioners"). The group flourished during the decade following the suppression of the Tiananmen democracy movement in June 1989, which many viewed as a hopeful development, showing that it was possible, even in the wake of the events of June 1989, to build a non-state-affiliated popular organization in China on a massive scale without state support. In 1999, however, the Party announced a total ban on Falun Gong, the implementation of which has resulted in the harassment, detention, and mental and physical abuse of large numbers of Falun Gong practitioners in official custody, and in some cases torture and death. The ban remains in force today, and authorities regularly intensify crackdowns on the Falun Gong movement around events the government deems to be sensitive, such as the Shanghai 2010 World Expo.

Chinese Government’s New Rhetoric on Compliance With International Human Rights Norms

Chinese officials appear to have adopted a new rhetorical strategy with respect to China’s compliance with international norms. In the past, Chinese officials often argued that it was necessary to carve out exceptions and waivers to the application of international norms to China. While stating their embrace of international norms in the abstract, for example, on free expression and the environment, they sought to make the case that, in practice, China deserved to be treated as an exception, due, for instance, to its status as a developing country. Now, however, official statements increasingly tend to declare the Chinese government’s compliance with international norms, even in the face of documented noncompliance. For example, in June 2010, the State Council Information Office released a white paper presenting "the true situation of the development and regulation of the Internet in China" to Chinese citizens and the international community. The white paper claims the government "guarantees citizens’ freedom of speech on the Internet" and that its model for regulating the Internet is "consistent with international practices." One implication of this new rhetorical tactic is that it seemingly relieves Chinese officials of the burden of arguing from the outset for exceptions and waivers to the application of international norms to China. Simply declaring compliance shifts the burden of persuasion to those who point out the Chinese government’s noncompliance, placing them in the position of critics of China, subject to accusations by Chinese officials of "finger-pointing," "China bashing," and "poisoning the atmosphere" for good relations with China. By adopting this new rhetorical approach, Chinese officials make respectful, open, and frank dialogue with China more difficult, and the approach itself underscores how important it is that Members of the U.S. Congress and Administration officials not uncritically accept Chinese officials’ declarations of compliance.

Chinese officials in the last year also increasingly have sought to portray the "Chinese model" (zhongguo moshi) as consistent with international human rights standards. In an April 2010 speech before the National People’s Congress Standing Committee, for example, State Council Information Office Director Wang Chen said the government is campaigning to gain global acceptance for its model of Internet control, having "engaged in dialogue and exchanges with more than 70 countries and international organizations," "countered Western enemy forces’ smears against us, and enhanced the international community’s acceptance and understanding of our model of managing the Internet." This new approach seeks to redefine the substance of international human rights standards in a manner that legitimizes the Chinese government’s noncompliance. This new approach appears to be connected with debates going on now within China over whether China should sign on to, or try to change, the rules of the international system.

Global Economic Conditions and the Expansion of State Control

The Communist Party is motivated to deliver employment and prosperity to inland and rural areas, and not just to coastal regions that already have benefited disproportionately from economic development, in part in order to demonstrate the Party’s ability to govern. The global economic downturn has dampened demand for Chinese exports, and that has made the delivery of employment and prosperity to inland and rural areas more challenging for the Party. In these areas, grievances over lax enforcement of health and safety standards and of environmental and worker rights protections have fueled discontent. The corruption and collusion between local businesses and local regulatory authorities that are associated with lax enforcement have undermined the reputation of the Party in these areas. In response, the leadership has resorted to expanded state economic and social control.

In the economic sphere, state-owned companies acquired private companies at a faster clip in the past year than previously. Flush with capital from an economic stimulus program of unprecedented magnitude and favored in the awarding of infrastructure projects, China’s state-owned enterprises have expanded easily and squeezed out private firms in some sectors. The need to address corruption and collusion between private firms and local regulatory officials, however, has allowed officials to cast expansion of state control as a method for improving accountability and the rule of law. In part because corruption and lax enforcement of health and safety standards and environmental and worker rights protections are the problems that fuel local discontent, Chinese citizens have not widely contested the Party’s justification of expanded state control in these terms.

At the same time, many Chinese firms, especially state-owned enterprises, continue to benefit from the Chinese government’s industrial policies that provide government subsidies, preferences, and other benefits. The government also has promoted "indigenous innovation," a massive government campaign to decrease reliance on foreign technology through industrial policies and to enhance China’s economy and national security, with the stated purpose of enabling China to become a global leader in technology by mid-century. Such policies have further facilitated the expansion of state control of the economy.

In the social sphere, China’s leaders over the last year sought to expand control by establishing or strengthening existing Party "branches" in non-governmental organizations, academic institutions, and residential communities. Local governments, charged with "maintaining social stability," established or strengthened existing "stability preservation offices" and established new "stability preservation funds" (weiwen jijin) from which they make payments to people with grievances in order to preempt their escalating disputes. Large numbers of petitioners availing themselves of China’s xinfang ("letters and visits") system for filing grievances against the government were harassed, abused, detained illegally, and involuntarily committed to psychiatric hospitals or sent to "reeducation through labor" facilities. Officials continued to use license suspension and disbarment as methods to control human rights lawyers who sought to represent clients in cases deemed by authorities to be politically sensitive.

Misapplication of Law as a Means of Control

The Communist Party and Chinese government are expanding and strengthening the capacity of law and regulation to serve as a means to control an increasing number of facets of life in China. Officials this past year sought to increase monitoring of communication technologies—the Internet and cell phones—that play a significant role in the daily lives of large numbers of Chinese citizens. Officials sought to make it easier for the government to identify the source of online content, by barring anonymous commenting, for example, and passed legal measures that add pressure on Internet companies to police the Internet for state secrets and for content that authorities allege may "infringe on the rights of others." While such moves may be aimed partly at legitimate targets of concern, including spam and defamatory content, in the Chinese context they also provide opportunities and incentives for officials and private companies to censor politically sensitive content.

Authorities increasingly have used the Law on the Control of the Exit and Entry of Citizens to manage dissent. Article 8 of the law allows the government to ban "persons whose exit from the country, in the opinion of the competent department . . . [would] be harmful to state security or cause a major loss to national interest." During this reporting year, authorities increasingly cited this provision to prevent rights defenders and advocates who are critical of the government from leaving China.

The Party and government also continued to use law to entrench a policy framework of state control over religion, as well as to exclude some religious communities from the limited but important protections afforded to state-sanctioned religious groups. In the past year, authorities made use of laws concerning property and financial assets to restrict the religious freedom of unregistered religious groups. President Hu Jintao used the powerful Fifth Tibet Work Forum platform to emphasize the Party’s role in controlling Tibetan Buddhism and the important role of law as a tool to enforce what the Party deems to be the "normal order" for the religion. The government and Party created increasing restraints on the exercise of freedom of religion for Tibetan Buddhists by strengthening the push to use policy and legal measures to shape and control the "normal order" for Tibetan Buddhism.

During this reporting year, China’s security and judicial institutions’ use of laws on "endangering state security"—a category of crimes that includes "subversion," "splittism," "leaking state secrets," and "inciting" subversion or splittism—infringed upon Chinese citizens’ constitutionally protected freedoms of speech, religious belief, association, and assembly. For example, the government has used the law on splittism to punish Tibetans who criticized or peacefully protested government policies and then used the law on "leaking state secrets" to punish Tibetans who attempted to share with other Tibetans information about incidents of repression and punishment. Authorities also issued regulations in the past year in Xinjiang to impose state-defined notions of "ethnic unity" and to tighten controls over online speech. The imprisonment of Uyghur Webmasters and a Uyghur journalist on charges of endangering state security, in connection with online postings and articles critical of conditions in Xinjiang, underscored authorities’ use of the Criminal Law to quell free expression. The imprisonment of Liu Xiaobo and other activists on inciting subversion and leaking state secrets charges after they peacefully criticized officials and the Party further underscored authorities’ use of the Criminal Law to quell free expression.

Prospects for the Rule of Law in China

Prospects for human rights and the rule of law in China depend not only on decisions taken by officials responsible for implementing law and protecting rights at the grassroots, but also on decisions taken at the highest levels of the Communist Party. The Party, with over 75 million members (roughly 5.7 percent of China’s total population), strives to maintain unchallenged rule over a country of more than 1.3 billion people. The Party stakes the legitimacy of its claim to rule China on its ability to provide both stability and prosperity to the Chinese people, and to "unify the country" (tongyi guojia). The Party leadership regards developments that could adversely affect China’s one-party system as potential threats to stability, prosperity, or unity. The rule of law, if implemented faithfully and fairly, should benefit not just those the Party favors. Some of China’s leaders, therefore, regard implementation of the rule of law as potentially diminishing the capacity of the Party to maintain control.

Three decades ago, the challenge that reformers within the Party faced was to find a way to advance market-oriented reforms while ensuring that economic development still bore the imprimatur of the Party. They succeeded. The economy boomed, and the Party received enough of the credit to enable it to maintain its hold on power. The challenge that reformers within the Party perceive today is in finding a way to advance the rule of law in a manner that results in the law still bearing the imprimatur of the Party. Over the last year, senior leaders have reiterated positions emphasizing the leading role of the Party, the need to adhere to the Party’s formulation of "socialist democracy," and the impossibility of implementing "Western-style" legal and political institutions.

Motivated by China’s dependence on foreign investment, China’s leaders have appeared to be more nimble in the commercial context to accept concepts and practices associated with so-called Western-style rule of law. Whether a decrease in China’s reliance on foreign investment ultimately will be associated with change or continuity in this regard remains to be seen. The findings of this Annual Report suggest, however, as the Commission reported in its last Annual Report, that the Party still "rejects the notion that the imperative to uphold the rule of law should preempt the Party’s role in guiding the functions of the state." Chinese leaders’ actions over the coming months will shed light on whether their stated commitment to the rule of law is real. The Commission and those who pay close attention to these issues in China will watch developments carefully.

In 2009, the Chinese government issued the 2009–2010 National Human Rights Action Plan that uses the language of human rights to cast an ambitious program for promoting the rights of Chinese citizens. The Action Plan has been described by some human rights advocates as signifying "remarkable progress" because in it the Chinese government articulates a clearly defined time period (2009–2010) for implementing a number of commitments to civil and political rights. The findings of this Annual Report document how the Party thus far has prioritized strengthening its grip on society over the implementation of the commitments to human rights and the rule of law set forth in the Chinese government’s own Action Plan. The Commission urges Members of the U.S. Congress and Administration officials to continue to inquire about the Chinese government’s progress in translating words into action and in securing for its citizens the improvements it has set forth in its Action Plan. To that end, this Annual Report and the information available on the Commission’s Web site may serve as useful resources.

I. Executive Summary

Freedom of Expression | Worker Rights | Criminal Justice | Freedom of Religion | Ethnic Minority Rights | Population Planning | Freedom of Residence and Movement | Status of Women | Human Trafficking | North Korean Refugees in China | Public Health | Climate Change and the Environment | Civil Society | Institutions of Democratic Governance | Commercial Rule of Law | Access to Justice | Xinjiang | Tibet | Developments in Hong Kong and Macau

FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

A summary of specific findings follows below for each section of this Annual Report, covering each area that the Commission monitors. In each area, the Commission has identified a set of issues that merit attention over the next year, and, in accordance with the Commission’s legislative mandate, submits for each a set of recommendations to the President and the Congress for legislative or executive action.

FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION

Findings

- During the Commission’s 2010 reporting year, Chinese authorities continued to maintain a wide range of restrictions that deny Chinese citizens their right to freedom of speech as guaranteed under China’s Constitution. Chinese officials continued to justify such restrictions on grounds such as protecting state security, minors, or public order. They also asserted that freedom of expression is protected in China, and that restrictions on free expression imposed by the Chinese government meet international standards. In practice, however, authorities continued to misuse vague criminal laws intended to protect state security to instead target peaceful speech critical of the Communist Party or Chinese government. In December 2009, a Beijing court sentenced prominent intellectual Liu Xiaobo to 11 years in prison for "inciting subversion of state power," the longest known sentence for this crime. Liu’s offenses were to publish essays online critical of the Communist Party and to help draft and circulate Charter 08, a treatise advocating political reform and human rights circulated online for signatures. Following demonstrations and riots in Urumqi, Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR), in 2009, authorities this past year used state security crimes to imprison a journalist and Web site administrators for expressing or failing to censor views critical of government policies in the region.

- While Chinese citizens now have unprecedented opportunities to express themselves through the Internet and other communication technologies, Chinese officials and private companies, as required by law, continued arbitrarily to remove or block political and religious content. They did so nontransparently and without clearly articulated standards. During the reporting year, Internet users and foreign media in China frequently found that politically sensitive news articles and discussions, including a domestic editorial cartoon that referred to the 1989 Tiananmen protests, had been removed or blocked from the Internet. Despite its noncompliance with international human rights standards, the Chinese government is waging a campaign to gain global acceptance for its model of Internet control.

- This past year, the controversy between the Chinese government and the U.S. company Google highlighted the potential for China’s censorship requirements to serve as a trade barrier and to cause companies to stop providing services to Chinese citizens, further limiting the free flow of information.

- In the XUAR, China’s maintenance of broad restrictions on the Internet, text messages, and international phone calls, put in place following the July 2009 demonstrations and riots in Urumqi and only gradually lifted starting in December 2009, illustrated the overbroad scope of China’s restrictions on free expression.

- The Communist Party continued to view the news media as a tool to serve the Party’s interests, in practice denying citizens their right to freedom of the press as guaranteed under China’s Constitution. Throughout the reporting year, the Commission observed numerous instances of officials reportedly prohibiting news media from publishing certain stories, such as a local media interview with U.S. President Barack Obama during his November 2009 trip to China, or punishing news media for publishing certain stories, such as a Chinese domestic joint media editorial criticizing and calling for reform of China’s household registration system.

- The government further strengthened its system of "prior restraints," by which the government may deny a person or group the use of a forum for expression in advance of the actual expression. Under this system, any person or group who wishes to publish a newspaper, host a Web site, or work as a journalist must receive permission from the government in the form of license or registration, and may also be required to meet other conditions, including political loyalty or financial requirements. In March 2010, an official announced the gov-ernment would be tightening entry requirements for journalists by requiring them to pass a qualification exam for which knowledge of "Chinese Communist Party journalism" and "Marxist views" of news will be required.

Recommendations

Members of the U.S. Congress and Administration officials are encouraged to:

- Raise concerns over the Chinese government’s efforts to gain global acceptance for its model of Internet control and the Chinese government’s blanket defense of restrictions on freedom of expression as being in line with international practice, without differentiating between restrictions for legitimate purposes, such as to protect minors, and restrictions for impermissible purposes, such as to silence dissent. Emphasize that such arguments undermine international human rights standards for free expression, particularly those contained in Article 19 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

- Engage in dialogue and exchanges with Chinese officials on the question of how governments can best ensure that restrictions on freedom of expression are not abused and do not exceed the scope necessary to protect state security, minors, and public order. Emphasize the importance of procedural protections such as public participation in formulation of restrictions on free expression, transparency regarding implementation of such restrictions, and independent judicial review of such restrictions. Reiterate Chinese officials’ own calls for greater transparency and public participation in lawmaking. Such discussions may be part of a broader discussion on how both the U.S. and Chinese governments can work together to ensure the protection of common interests, including protecting minors, computer security, and privacy with regard to the Internet.

- Support the research and development of technologies that enable Chinese citizens to access and share political and religious content that they are entitled to access and share under international human rights standards but that is blocked by Chinese officials. Support tools and practices that enable Chinese citizens to access and share such content in a way that ensures their security and privacy.

- Call for the release of Liu Xiaobo and other political prisoners imprisoned on charges of endangering state security and other crimes but whose only offenses were to peacefully express support for political reform or criticism of government policies, including: Tan Zuoren (sentenced in February 2010 to five years in prison after using the Internet to organize an independent investigation into school collapses in an earth-quake) and Huang Qi (sentenced in November 2009 to three years in prison for using his human rights Web site to advocate for parents of earthquake victims).

WORKER RIGHTS

Findings

- Workers in China still are not guaranteed, either by law or in practice, full worker rights in accordance with international standards, including the right to organize into independent unions. The All-China Federation of Trade Unions (ACFTU), the official union under the direction of the Communist Party, is the only legal trade union organization in China. All lower level unions must be affiliated with the ACFTU and must align with its overarching political concerns of maintaining "social stability" and economic growth.

- Labor disputes and officials’ concern with maintaining "social stability" intensified over this reporting year as layoffs, wage arrears, and poor and unsafe working conditions persisted. Growing concern on the part of local governments to maintain economic growth and employment continued to prompt some localities to respond to labor laws that took effect in 2008 (the Labor Contract Law, Employment Promotion Law, and Labor Dispute Mediation and Arbitration Law) with local opinions and regulations of their own that weakened some employee-friendly aspects of these laws. Interpretation of these laws across localities has not been consistent, leading to their "regionalization" and "loopholization."

- During the spring and summer of 2010, Chinese and international media and non-governmental organizations reported on a spate of worker actions—from a succession of strikes to suicides at a factory compound—at various enterprises in China, mostly foreign invested, that garnered attention in China and around the world. Unofficial reports suggest that the striking workers’ primary demand was higher wages. In a number of strikes workers called for existing All-China Federation of Trade Unions (ACFTU)-affiliated unions to behave more independently within the confines of Chinese law. Some of the strikes and demands for higher wages during 2010 may not be a sign of continued weakness on the part of workers vis-a`-vis management. Rather, they may reveal that workers in some cases have been emboldened not only by worker rights codified in labor laws that took effect in 2008, but also by a tighter labor market.

- In response to collective labor action that was organized and large-scale, the Chinese government continued to redirect labor disputes away from the formal channels of arbitration and litigation toward more "flexible" and "grassroots-level" negotiation and mediation. These forms of dispute resolution often relied on coordination among levels of local government (e.g., provincial, city, town, etc.), involving local government and Party units, the official trade union, and the police and security apparatus.

- Backlogs in the handling of labor dispute cases continued to exceed time limits mandated by law. In addition to large increases in arbitrated cases, labor dispute cases also continued to deluge Chinese courts. In some cases, these disputes were the result of strong dissatisfaction with arbitration proceedings, as most arbitrated cases can be reviewed in a court if either side is dissatisfied. In other cases, the increase reflected the strong and growing rights consciousness of Chinese workers who turned to new protections offered in labor laws that took effect in 2008.

- Migrant workers continued to face discrimination in urban areas, and their children still faced difficulties accessing city schools. Employment discrimination more generally continued to be a serious problem, and plaintiffs brought a growing number of anti-discrimination suits under China’s Employment Promotion Law.

- During the 2010 reporting year, enforcement of China’s Labor Contract Law continued to be uneven or selective. Even as reported statistics show increases in the number of labor contracts signed, formal employment in China continues to erode, especially for unskilled urban workers and rural migrants. There have been reports of employers concluding multiple contracts per worker in order to avoid payment of overtime; replacing older workers with younger workers to avoid longer-term contracts; using contract expiration as a method for laying off formal employees during economic slowdowns; and refusing to hire employees who insist on exercising their right to conclude a labor contract. Studies by Chinese researchers suggest that substantial numbers of Chinese workers report that their actual work hours are different from the hours specified in their labor contracts.

- The ACFTU during the reporting year has appeared to be more willing to address the issue of worker representation. One ACFTU official stated that, "in mitigating labour disputes, the fundamental issue is to establish a collective bargaining system that would allow labour disputes to be managed and resolved within the enterprise." Following worker strikes at a number of foreign-invested manufacturing facilities during this reporting year, officials in the southern Chinese province of Guangdong accelerated action on draft Regulations on Enterprise Democratic Management. In September, the Guangdong People’s Congress Standing Committee reportedly delayed further deliberation of the draft. Heavy lobbying by members of the Hong Kong industrial community, many of whom own and operate factories in Southern China, reportedly played a role in the Standing Committee’s decision. However, Guangdong’s draft regulations are particularly noteworthy in that they specifically grant workers the right to demand the initiation of collective wage consultations—a right that typically has been reserved for unions. Guangdong and other localities, including Beijing, Hainan, and Tianjin, also have issued guidance notices and regulations specifying the legal rights of parties involved in collective consultations.

- The Chinese government’s complicated and time-consuming work-related injury compensation procedure continued to be a major problem for China’s injured workers. The process is further complicated for migrant workers who may already have left their jobs and moved to another location by the time clinical symptoms surface. Workers more generally also continued to face persistent occupational safety issues. Collusion between mine operators and local government officials reportedly remains widespread, leading to lax enforcement of health and safety standards. Prohibitions on independent organizing limit workers’ ability to promote safer working conditions.

- China’s new generation of migrant workers, unlike their parents, have higher expectations with regard to wages and labor rights. Younger workers, born in the 1980s and 1990s, reportedly were at the forefront of worker strikes that took place this past year across China. Together, they make up about 100 million of China’s total pool of migrant workers. In an essay describing the characteristics of the new generation of migrant workers, China’s Agricultural Minister Han Changfu pointed out that many of these young workers have never laid down roots, are better educated, are the only child in the family, and are more likely to "demand, like their urban peers, equal em-ployment, equal access to social services, and even the obtainment of equal political rights."

- In 2010, the Commission followed several reports alleging that Chinese state-owned enterprises utilized prison labor sent from China at their overseas worksites. Chinese prisoners reportedly have worked on housing and other infrastructure projects such as ports and railroads outside of China. One report indicated that transporting workers from China is standard practice for some Chinese companies operating outside of China and sometimes includes prisoners and those who are on parole. China’s Law on the Control of the Exit and Entry of Citizens states that "approval to exit from the country shall not be granted to . . . convicted persons serving their sentences."

Recommendations

Members of the U.S. Congress and Administration officials are encouraged to:

- Support projects promoting legal reform intended to ensure that labor laws and regulations reflect internationally recognized labor principles. Prioritize projects that do not focus only on legislative drafting and regulatory development, but that analyze implementation and measure progress in terms of compliance with internationally recognized labor principles at the grassroots.

- Support multi-year pilot projects that showcase the experience of collective bargaining in action for both Chinese workers and trade union officials; and identify local trade union offices found to be more open to collective bargaining and focus pilot projects in their locales. Where possible, prioritize programs that demonstrate the ability to conduct collective bargaining pilot projects even in factories that do not have an official union presence. Encourage the expansion of exchanges between Chinese labor rights advocates in NGOs, the bar, academia, and the official trade union, and U.S. collective bargaining practitioners. Prioritize exchanges that emphasize face-to-face meetings with hands-on practitioners and trainers.

- Encourage research that identifies factors underlying inconsistency in enforcement of labor laws and regulations. This includes projects that prioritize the large-scale compilation and analysis of Chinese labor dispute litigation and arbitration cases, and guidance documents issued by and to courts at the provincial level and below, leading ultimately to the publication and dissemination of Chinese language casebooks that may be used as a common reference resource by workers, arbitrators, judges, lawyers, employers, union officials, and law schools in China.

- Support capacity-building programs to strengthen Chinese labor and legal aid organizations involved in defending the rights of workers. Encourage Chinese officials at local levels to develop, maintain, and deepen relationships with labor organizations based in Hong Kong and elsewhere, and to invite these groups to increase the number of training programs on the mainland. Support programs that train workers in ways to identify problems at the factory floor level, equipping them with skills and problem-solving training so they can relate their concerns to employers effectively.

- Where appropriate, share the United States’ ongoing experience and efforts in protecting worker rights—via legal, regulatory, or non-governmental means—with Chinese officials. Facilitate site visits and other exchanges for Chinese officials to observe and share ideas with U.S. labor rights groups, lawyers, the U.S. Department of Labor (USDOL), and other regulatory agencies at all levels of government that work on labor issues. Encourage discussion on the value of constructive interactions among labor non-governmental organizations, workers, employers, and government agencies; encourage exchanges that emphasize the importance of government transparency in developing stable labor relations and in ensuring full and fair enforcement of labor laws. Support USDOL’s exchanges with Chi-na’s Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security (MOHRSS) regarding setting and enforcing minimum wage standards, strengthening social insurance, improving employment statistics, and promoting social dialogue. Support the annual labor dialogue with China that USDOL started this year and plans for further progress in bilateral labor relations.

CRIMINAL JUSTICE

Findings

- During the Commission’s 2010 reporting year, the Chinese government took steps to limit the prevalence of coerced confessions and illegally obtained evidence within the judicial system. In May 2010, five Chinese law enforcement agencies announced two new regulations that intend to limit the use of torture by police and prosecutors in criminal, particularly death penalty, cases. Over the 2010 reporting year, police torture and coerced confessions continued to be widely reported by international and domestic organizations.

- Citing concerns over social tensions, Chinese authorities have promoted local and nationwide anti-crime campaigns to stem reported rising crime rates. In June 2010, China launched the fourth round of its national "strike hard" campaign in a massive seven-month crackdown on violent crimes and escalating social conflicts. "Strike hard" campaigns and anti-crime crackdowns have been tied to unusually harsh law enforcement tactics, quick trials, and violations of China’s own criminal procedure laws and regulations.

- During this reporting year, Chinese judicial officials contravened provisions in China’s Criminal Procedure Law that require courts to provide access to criminal trials for any observer, regardless of citizenship, except where the law specifically prohibits an open trial.

- Harassment and intimidation of human rights advocates by Chinese government officials continued during this reporting year. Public security authorities and unofficial personnel unlawfully monitored rights defenders, petitioners, religious adherents, human rights lawyers, and their family members, and subjected them to periodic illegal home confinement. Such mistreatment and abuse was evident particularly in the leadup to sensitive dates and events, such as U.S. President Barack Obama’s visit in November 2009 and the Shanghai 2010 World Expo.

- Chinese officials continued to use various forms of extralegal detention against Chinese citizens, including petitioners, peaceful protesters, and other individuals considered to be "involved in issues deemed sensitive by authorities." Some of those arbitrarily detained were held in psychiatric hospitals or extralegal detention facilities, such as "black jails," and subjected to treatment inconsistent with international standards and protections found under China’s Constitution and Criminal Procedure Law.

- Chinese criminal defense lawyers continue to confront obstacles to practicing law without judicial interference or fear of prosecution. In politically sensitive cases throughout China, criminal defense attorneys routinely faced harassment and abuse. Some suspects and defendants in sensitive cases were not able to have counsel of their own choosing; some were compelled to accept government-appointed defense counsel. Abuses of Article 306 of the Criminal Law, which assigns criminal liability to lawyers that force or induce a witness to change his or her testimony or falsify evidence, continue to hamper the effectiveness of criminal defense.

- In August 2010, the National People’s Congress reviewed the first draft of the proposed eighth amendment to China’s Criminal Law, which reportedly calls for reducing the current 68 crimes punishable by death to 55 crimes. The reduction would signal the first time the Chinese government has reduced the number of crimes punishable by capital punishment since the Criminal Law was enacted in 1979.

Recommendations

Members of the U.S. Congress and Administration officials are encouraged to:

- Press the Chinese government to adopt the recommendation of the UN Committee against Torture to investigate and disclose the existence of black jails and other secret detention facilities, as a first step toward abolishing such forms of extralegal detention. Ask the Chinese government to extend an invitation to the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention to visit China.

- Call on the Chinese government to guarantee the rights of criminal suspects and defendants in accordance with international human rights standards and provide the international community with a specific timetable for its ratification of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which the Chinese government signed in 1998, but has not ratified. Press the Chinese government to adhere to protections for criminal suspects and defendants asserted in its 2009–2010 National Human Rights Action Plan, and encourage the publication and broad dissemination of fully detailed reports and updates on local government implementation of the Action Plan.

- Urge the Chinese government to amend its Criminal Procedure Law to reflect the enhanced protections and rights for lawyers and detained suspects contained in the 2008 revision of the Lawyers Law. Encourage Chinese officials to commit to a specific timetable for revision and implementation of the revised Criminal Procedure Law.

- Make clear that the international community regards as laudable the commitments to fair trial rights and detainee rights the Chinese government made in its 2009–2010 National Human Rights Action Plan. Request information on the formalization of those commitments into laws and regulations and on what further steps it will take to ensure their successful implementation, and support bilateral and multilateral cooperation and dialogue to support such efforts.

FREEDOM OF RELIGION

Findings

- China’s Constitution guarantees "freedom of religious belief" but protects only "normal religious activities," and the government’s restrictive framework toward religion continued in the past year to prevent Chinese citizens from exercising their right to freedom of religion in line with international human rights standards.

- Some Chinese citizens had space to practice their religion, but the Chinese government continued to exert tight control over the affairs of state-sanctioned religious communities and to repress religious and spiritual activities falling outside the scope of Communist Party-sanctioned practice. The government maintained requirements that religious organizations register with the government and submit to the leadership of "patriotic religious associations" created by the Party to lead China’s five recognized religions: Buddhism, Catholicism, Taoism, Islam, and Protestantism.

- Unregistered groups risked harassment, detention, imprisonment, and other abuses, as did members of registered groups deemed to deviate from state-sanctioned activities. Variations in implementation allowed some unregistered groups to function in China, but such tolerance was arbitrary and did not amount to the full protection of these groups’ rights.

- As leadership in the State Administration for Religious Affairs changed in the past year, authorities continued to affirm policies of control over religion. Despite articulating a "positive role" for religious communities in China, officials did not then use the notion of this "positive role" to promote religious freedom, but rather used the sentiment to bolster support for state economic and social goals.

- The government continued to use law to control religious practice rather than protect the religious freedom of all Chinese citizens. The government continued to pass legal measures that provide some legal protections for registered religious communities, but condition many activities on government oversight or approval and exclude unregistered groups from limited state protections.

- China’s diverse religious communities faced various state controls over their affairs, and in some cases, harassment, detention, and other abuses. Authorities continued to control Buddhist institutions and practices and take steps to curb "unauthorized" Buddhist temples. The government and Party placed increasing restraints on the exercise of freedom of religion for Tibetan Buddhists and continued to punish Tibetan Buddhists for openly expressing their devotion to the Dalai Lama. The government and Party continued to deny members of the registered Catholic church the freedom to recognize the authority of the Holy See to select Chinese bishops, while authorities continued to harass and hold some unregistered priests and bishops under surveillance or in detention. Authorities across the country used the specter of "extremism" to bolster state interference in how Muslims interpreted and practiced their religion. Conditions for religious freedom for Muslims in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region continued to worsen as authorities integrated controls over Muslims’ religious freedom into far-reaching security crackdowns. Chinese authorities continued to impose state-defined interpretations of theology on registered Protestant communities and to harass and, in some cases, detain and imprison members of unregis-tered Protestant churches, while also razing church property. Authorities maintained controls over Taoist activities and took steps to curb "feudal superstitious activities."

- During this reporting year, the Chinese government maintained a "strike hard" campaign that it has carried out against Falun Gong practitioners for more than a decade, continuing its harassment and intimidation of Falun Gong practitioners and lawyers who defend Falun Gong clients. Local governments throughout the Shanghai municipal area and surrounding provinces reported mobilizing security forces to target Falun Gong practitioners in preparation for the Shanghai 2010 World Expo, and the 6–10 Office, whose activities continued to expand during this reporting year, spearheaded the Shanghai Expo crackdown.

Recommendations

Members of the U.S. Congress and Administration officials are encouraged to:

- Call on the Chinese government to guarantee to all citizens freedom of religion in accordance with Article 18 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and to remove its framework for recognizing only select religious communities for limited state protections. Stress to Chinese authorities that all citizens are entitled to enjoy freedom of religion as a fundamental human right, regardless of whether they practice religion in a way deemed to contribute to state economic and social goals.

- Call for the release of Chinese citizens confined, detained, or imprisoned in retaliation for pursuing their right to freedom of religion (including the right to hold and exercise spiritual beliefs). Such prisoners include: Sonam Lhatso (Tibetan Buddhist nun sentenced in 2009 to 10 years’ imprisonment after she and other nuns staged a protest calling for Tibetan independence and the Dalai Lama’s long life and return to Tibet); Su Zhimin (an unregistered Catholic bishop who "disappeared" after being taken into police custody in 1996); Wang Zhiwen (Falun Gong practitioner serving a 16-year sentence for organizing peaceful protests by Falun Gong practitioners in 1999); Yusufjan and Memetjan (university students who are members of a Muslim religious group and were detained in May 2009 when members of the group met on a university campus); Yang Rongli and Wang Xiaoguang (house church pastors sentenced to 7 and 3 years, respectively, in 2009 in connection to their activities leading an unregistered congregation), as well as other prisoners mentioned in this report and in the Commission’s Political Prisoner Database.

- Call on the Chinese government to end interference in the internal affairs of religious communities and stress to the Chinese government that freedom of religion includes: the freedom of Buddhists to carry out activities in temples independent of state controls over religion, and the freedom of Tibetan Buddhists to express openly their respect or devotion to Tibetan Buddhist teachers, including the Dalai Lama; the freedom of Catholics to recognize the authority of the Pope to make bishop appointments; the freedom of Taoists to interpret their faith free from state efforts to ban practices deemed as "feudal superstitions"; the right of Falun Gong practitioners to freely practice Falun Gong inside China; the right of Muslims to interpret theology free from state interference and not face curbs on their internationally protected right to freedom of religion in the name of upholding "stability"; and the right of Protestants to worship free from state controls over doctrine and to worship in unregistered house churches, free from harassment, detention, and other abuses.

- Support initiatives to provide technical assistance to the Chinese government in drafting legal provisions that protect, rather than restrain, freedom of religion for all Chinese citizens. Support training classes for Chinese officials on international human rights standards for the protection of freedom of religion.

- Support non-governmental organizations that collect information on conditions for religious freedom in China and that inform Chinese citizens of how to defend their right to freedom of religion against Chinese government abuses.

ETHNIC MINORITY RIGHTS

Findings

- Chinese law provides for a system of "regional ethnic autonomy" in designated areas with ethnic minority populations, but shortcomings in the substance and implementation of this system have prevented ethnic minorities from enjoying meaningful autonomy in practice. The Chinese government maintained policies in the past year that prevented ethnic minorities from "administering their internal affairs" as guaranteed in Chinese law and from enjoying their rights in line with international human rights standards. While the Chinese government maintained some protections in law and practice for ethnic minority rights, it continued to impose the fundamental terms upon which Chinese citizens could express their ethnicity and to prevent ethnic minorities from enjoying their cultures, religions, and languages free from state interference, in violation of international human rights standards.

- Among the 55 groups the Chinese government designates as minority ethnic groups, state repression was harshest toward groups deemed to challenge state authority, especially in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, and Tibet Autonomous Region and other Tibetan autonomous areas.

- The Chinese government continued in the past year to assert the effectiveness of state laws and policies in upholding the rights of ethnic minorities, following domestic protests and international criticism of the government’s treatment of ethnic minorities. The Chinese government and Communist Party strengthened "ethnic unity" campaigns as a vehicle for spreading state policy on ethnic issues throughout Chinese society and for imposing state-defined interpretations of the history, relations, and current conditions of ethnic groups in China.

- Chinese leaders pledged to refine and improve conditions for ethnic minorities, within the parameters of existing Party policy, issuing some policy documents in the past year which may bring mixed results in the protection of ethnic minorities’ rights. The Chinese government’s 2009–2010 National Human Rights Action Plan issued in April 2009 outlined measures to support ethnic minority populations in China.

- The Chinese government maintained economic development policies that prioritize state economic goals over the protection of ethnic minorities’ rights. Despite bringing some benefits to ethnic minority areas and residents, such policies also have conflicted with ethnic minorities’ rights to maintain traditional livelihoods, spurred migration to ethnic minority regions, promoted unequal allocation of resources favoring Han Chinese, intensified linguistic and assimilation pressures on local communities, and resulted in environmental damage.

- Authorities in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region continued in the past year to restrict independent expressions of ethnic identity among Mongols and to interfere with their preservation of traditional livelihoods, while enforcing campaigns to promote stability and ethnic unity.

Recommendations

Members of the U.S. Congress and Administration officials are encouraged to:

- Fund rule-of-law programs and exchange programs that raise awareness among Chinese leaders of different models for governance that protect ethnic minorities’ rights and allow them to exercise meaningful autonomy over their affairs, in line with both domestic Chinese law and international human rights standards. Fund programs that promote models for sustainable development that draw on participation from ethnic minority communities.

- Support non-governmental organizations that address human rights conditions for ethnic minorities in China to enable them to continue their research and develop programs to help ethnic minorities increase their capacity to protect their rights. Encourage such organizations to develop training pro-grams to promote sustainable development among ethnic minorities, programs to protect ethnic minority languages and cultures, and programs that research rights abuses in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region. Encourage broader human rights and rule-of-law programs that operate in China to develop programs to address issues affecting ethnic minorities in China.

- Call on the Chinese government to release people detained or imprisoned for advocating for the rights of ethnic minority citizens, including Mongol rights advocate Hada (serving a 15-year sentence after pursuing activities to promote Mongols’ rights and democracy) and other prisoners mentioned in this report and in the Commission’s Political Prisoner Database.

- Support organizations that can monitor the Chinese government’s compliance with stated commitments to protect ethnic minorities’ rights, including as articulated in the government’s 2009–2010 National Human Rights Action Plan and in international law that the Chinese government is bound to uphold. Provide support for organizations that can provide assistance in implementing programs in a manner that draws on participation from communities involved and ensures the protection of their rights.

POPULATION PLANNING

Findings

- Chinese authorities continued to implement population planning policies that interfere with and control the reproductive lives of women, employing various methods including fines, cancellation of state benefits and permits, forced sterilization, forced abortion, arbitrary detention, and other abuses.

- Human rights abuses by officials charged with implementing population planning policies continue despite provisions in Chinese law that prohibit such abuses. China’s 2002 Population and Family Planning Law (PFPL) states in Article 4 that officials "shall perform their administrative duties strictly in accordance with the law, and enforce the law in a civil manner, and they may not infringe upon the legitimate rights and interests of citizens." The PFPL also states in Article 39 that "any functionary of a State organ who commits one of the following acts in the work of family planning, if the act constitutes a crime, shall be investigated for criminal liability in accordance with the law; if it does not constitute a crime, he shall be given an administrative sanction with law; his unlawful gains, if any, shall be confiscated: (1) infringing on a citizen’s personal rights, property rights, or other legitimate rights and interests; (2) abusing his power, neglecting his duty, or engaging in malpractices for personal gain . . . ."

- The Commission observed in 2010 a greater number of reports confirming its 2009 finding that some local governments are specifically targeting migrant workers for forced abortions.

- The Commission noted that increased public awareness of the demographic and social consequences of the Chinese government’s population planning policy in the 2010 reporting year led to public debate among Chinese experts and government officials regarding the need for policy reform. However, top Communist Party and government leaders continue to publicly defend the policy and rule out reform in the near term.

- The Chinese government’s population planning policies continue to exacerbate the country’s highly skewed sex ratio. Reports in the last year, however, emphasized how population planning policies exacerbate other demographic challenges as well, including a rapidly aging population and a decline in working age population.

Recommendations

Members of the U.S. Congress and Administration officials are encouraged to:

- Urge the Chinese government to vigorously enforce provisions under Chinese law that provide for punishments of officials and other individuals who violate the rights of citizens when implementing population planning policies. Urge the Chinese government to establish penalties, including specific criminal and financial penalties, for officials and individuals found to commit abuses such as coercive abortion and coercive sterilization, which continue in China despite provisions under existing laws and regulations intended to prohibit them.

- Urge Chinese officials to cease coercive methods of enforcing birth control quotas. Urge the Chinese government to dismantle coercive population controls and provide greater reproductive freedom and privacy for women.

- Call on Chinese officials to permit greater public discussion and debate concerning population planning policies and to demonstrate greater responsiveness to public concerns. Support the development of programs and international cooperation on legal aid and training programs that help citizens pursue compensation under China’s newly amended State Compensation Law, and other remedies against the state for injury suffered as a result of official abuse related to China’s population planning policies.

FREEDOM OF RESIDENCE AND MOVEMENT

Findings

- The Chinese government’s household registration (hukou) system, first implemented in the 1950s, continues to limit the right of Chinese citizens formally to establish their permanent place of residence. Implementation and enforcement of some hukou measures resulted in discrimination against rural hukou holders who migrate to urban areas. Most frequently, hukou is used to deny social benefits such as education and subsidized healthcare to migrant workers in cities. The discriminatory effects are especially prominent in the area of education.

- Authorities continued during the Commission’s 2010 reporting period to relax some hukou restrictions consistent with earlier reforms. Guangzhou municipality instituted reforms to unify rural and urban hukou into a single residential hukou. Chongqing municipality initiated gradual voluntary hukou reforms aimed at increasing the percentage of urban hukou holders. The effects of these reforms are unclear pending ongoing implementation.

- The Chinese government and Communist Party exercised strict control over public debate on hukou reforms during the 2010 reporting year. Authorities removed from the Internet a joint editorial published by 13 newspapers that decried the hukou system as corrupt and in need of speedy reform. A coauthor of the piece was forced to resign his position as deputy editor of a major newspaper.

- The Chinese government continued to impose restrictions on Chinese citizens’ right to travel in a manner that is inconsistent with international human rights standards. During the Commission’s 2010 reporting year, Chinese government authorities arbitrarily barred rights defenders, advocates, and critics from entering and leaving China. Officials refused to renew passports to rights advocates and subsequently cited invalid passports as grounds to prevent entry. In some instances, no reasons for the travel ban were provided.

- The Chinese government continued to use coercive measures to restrict Chinese advocates’, rights defenders’, and dissidents’ liberty of movement within China, especially during politically sensitive periods, including the months leading up to the Shanghai 2010 World Expo. Authorities used measures such as surveillance, police presence outside of one’s home, "invitations" to tea with police, forced trips, detention, removal from one’s home, reeducation through labor, and imprisonment.

Recommendations

Members of the U.S. Congress and Administration officials are encouraged to:

- Support programs, organizations, and exchanges with Chinese policymakers and academic institutions engaged in research and outreach to migrant workers that provide legal assistance to migrant workers and encourage policy debates on the hukou system.

- Encourage U.S. academic and public policy institutions and experts to consult with the Commission on avenues for outreach to Chinese academic and public policy figures engaged in policy debates on reform of the hukou system.

- Stress to Chinese government officials that the Chinese government’s noncompliance with international standards regarding freedom of movement inside China negatively impacts confidence outside China in the Chinese government’s commitment to international standards more generally.

- Raise specifically Chinese authorities’ restriction on the liberty of movement of rights defenders, advocates, and critics including writer Liao Yiwu, advocate Feng Zhenghu, economist Ilham Tohti, professor Cui Weiping, writer Liu Xia (wife of imprisoned intellectual Liu Xiaobo), and democracy advocates Ding Zilin, Qi Zhiyong, and Li Hai.

STATUS OF WOMEN

Findings

- Chinese officials continued to promote existing laws that aim to protect women’s rights, including the amended Law on the Protection of Women’s Rights and Interests and the amended Marriage Law; however, inconsistent interpretation, selective implementation, and selective enforcement of these laws across localities limit progress on concrete protections of women’s rights.

- Recent statistics show increases in women holding positions at the central, provincial, and municipal levels of government.

- Female political representation at the village level remains low, due in part to the traditional patriarchal system still in play in parts of rural China. Villages typically have a high rate of "self-governance" with regard to issues such as land contracts, profit distribution from collectives, and land requisition compensation, and with limited decisionmaking power in village committees, women’s interests are less likely to be represented in village rules and regulations, as well as in land disputes.

- The Chinese government is committed under Article 7 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights and Article 11 of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women to ensuring gender equality in employment. While China’s existing laws such as the Labor Law, amended Law on the Protection of Women’s Rights and Interests, and Employment Promotion Law prohibit gender discrimination, they lack clear definitions and enforcement mechanisms, which weakens their effectiveness. Women continue to experience widespread discrimination in areas including recruitment, wages, and retirement. The Shenzhen Municipal Women’s Federation announced draft regulations during the Commission’s 2010 reporting year to promote gender equality in employment in the Shenzhen Special Economic Zone.